The story of how an old house in East London was saved from demolition and revived

I have spent most of my adult life fighting developers – their destructive avarice, their desire to clear and make a clean slate of building plots – and their race for profits.

During my nineteen years running the Spitalfields Trust for its Trustees, this was a constant threat that we faced.

In 2007 I was campaigning to save two short terraces of late Georgian houses on Turner and Varden Streets in Whitechapel, East London.

Originally part of the Royal London Hospital Estate, they were built between 1807 and 1812.

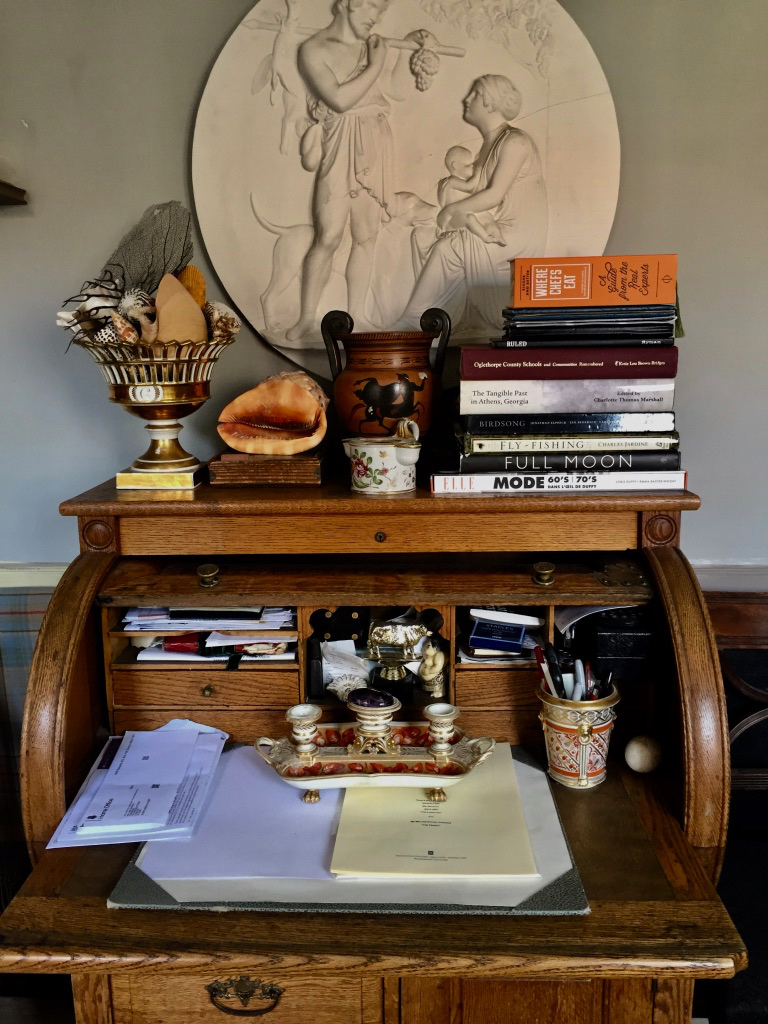

Sculpture pantheon at the rear of the house

At first we were taking on Queen Mary University, the owners, and the university’s chosen developers, the ‘London Development Agency’ or LDA.

Front room, ground floor, taken during the move to a much older house in Cumbria

Queen Mary was less than helpful, they wanted to replace these Georgian houses with new university buildings, getting the LDA to do their dirty work. But in the end an alternative site was found and the LDA came around to our point of view and began working in tandem with the Spitalfields Trust to save the houses.

The buildings were not considered worthy of listing by English Heritage, who weren’t prepared to inspect their empty interiors, citing the fact that they were infested by colonies of pigeons. But the houses on nearby Walden Street – built some 5 years later than the terraces in Turner and Varden Streets and with fewer original internal fittings – were already listed!

Back room, ground floor

In the end this poor show by English Heritage’s listing team would prove to be a godsend, enabling the Spitalfields Trust to repair and extend these houses without the narrow restrictions imposed by listing.

Rear extension, ground floor

We were now free to give these houses a much greater charm with the addition of mansard roofs and weatherboarded rear extensions. Since they sat in a Conservation Area, building regulations permitted traditional single glazing as long as we insulated their new roofs and rear wings to death. The Trust got going on 9 of the houses with the professional services of the architect Paul Latham.

Two houses were set aside to be sold at private auction a couple of years later and that is when my partner Harvey Cabaniss and I bought ours, which dated from 1809. Using my own architectural template we replaced the 1970’s roof with a mansard and built a much larger rear wing helping to hide the 1980s eyesore building on an adjacent 2nd World War bombsite.

This was going to be fun – for now I had the room to build a back staircase in a London house. I had always wanted a backstairs!

The 80s eyesore

Basement kitchen, back of house

Basement kitchen, back of house

Basement kitchen, back of house

Basement front room

basement front room

The house still had paneling to ground and first floors – but all the fireplaces were missing.

basement front room

Ebay supplied us with reasonably priced early 19th century hob grates and numerous other fittings.

Rear extension, first floor

Rear extension, first floor

Rear extension, first floor

Once the building works were finished, decoration and furnishing could proceed.

First floor bedroom, quarters for Tim’s mother

Put-together fireplace

First floor bathroom

First floor bathroom

Backstairs

Attics under new mansard roof

Attic

Top floor bedroom

top floor bedroom, invented fireplace

top floor bedroom, teddies, waiting

Top floor bathroom

Laundry drying

head of attic stairs

A lean-to conservatory cum glasshouse became my own little sculpture gallery, housing my collection of plaster casts.

My odd assortment of casts includes:

In one corner of the window, a 19th century Dutch cast of Socrates from Leiden University sits on top of a 19th century French museum architectural cast of the Ionic Order.

Amongst other things on the rear wall are an 18th century bulcrania (ram’s skull), an architectural oddment from James Paine’s Belford Hall in Northumberland, beneath it is a fragment of plaster frieze from John Dobson’s early nineteenth century alterations at Belford.

On the table are a pair of 19th century plaster busts: seen on the left, Sir Walter Scott, after Sir Francis Chantrey.

The table is a composite reusing an old French marble top, made by me and painted with a Greek key frieze beneath the top. A collection of 19th century toleware tin storage canisters sits on top of the glazed Gothic bookcase – in the eighteenth century these would have adorned a tea and coffee merchant’s Shop.

The bobt writes: The Spitalfields Trust was founded in 1977 by Mark Girouard, Dan Cruickshank, Raphael Samuel and a group of archtectural historians and preservationists who determined to stop the demolition of the few remaining streets of outstanding early Georgian houses in the Spitalfields Market area of East London. What began as a maverick gang of enthusiasts using direct action to halt the approaching bulldozers has metamorphosed into an established architectural charity taking grants from various heritage bodies to support its continuing work in England and Wales. earlier projects included Malplaquet House in Stepney, whose pioneering first owners were Tim Knox of the Royal Collections Trust and the landscape and garden designer Todd Longstaffe Gowan, and its next door neighbour on the Stepney Road, home to the arts historian and blogger Charles Saumerez Smith and jewellery designer Romilly Savage ( both on the bibleofbritishtaste.com ).

Sir Walter

Huge thanks to Tim Whittaker and Harvey Cabaniss, now happily removed to Newbiggin in Cumbria. Older pictures of this Whitechapel house with its full complement of furniture and of their new old house, a work in progress, are @timjohnwhittaker

All photographs copyright bibleofbritishtaste.com

Speechless. Charming seems trite but it’s spot on. In love.

Lovely story and a home full of wonderful memories! Beautiful!

Hard to tell the new from the old, so sensitively has this been done. Altogether a beautifully quiet piece of work. Lucky house in Newbiggin!

Loved reading this story! Thanks for the photos and for sharing it!

Hard to believe such wonderful houses could have been demolished! Beautifully restored.

What is the name of your green grey paint..used in much of your house eg top of the stairs? I must start looking for casts!

Wonderful.Such sensitive and

accomplished work. Do you ever do open days?

I just read about “New Road” in a photo book from Robert O’Byrne/Simon Brown (Gerstenberg). Very nice to see more beautiful pictures of the interior here!

Tim should have a medal.

I have noted his love of plasterwork and in particular Sir Walter Scott who was a friend and artistic subject of Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey who was my 4Xggrandfather and he can be linked to Spitalfields. His illigitimate son George married Emma Susannah Rosé (also spelt sometimes as Rozee/Royce/Rosee/Rosigh etc!!) who is of Huguenot descent. Her family lived in the East End. On the Huguenot list Philip Rosé (Roose) is mentioned as being a silk weaver in Spitalfields in 1685, plus Emma Susannah’s grandfather George Rosé (Rosee) is listed as a silk weaver in Fournier Street, Spitalfields.

Cannot understand why anyone would want to demolish these wonderful old houses.

And replace them with some ugly glass monstrosity.