From a temporary gallery arranged in the downstairs rooms of her house in Stepney, Romilly Saumarez Smith has just sold her latest jewellery collection. ‘That collection is done now, we’ll make up the orders but then we’ll go on to the next one, and I’ve got another idea for after that – my thinking is onto the next thing, now,’ she said when I saw her there a couple of weeks ago.

This house is another of her works of art. The calm order of the rooms here belies the fact that in the year 2000, it was a no more than a brick carcass. Joinery, staircase, windows, chimneys and even the attic storey were gone.

‘When we first got here you could drive through the middle of the house to the space where they fitted the exhaust pipes, and there were shops on the front,’ she says. The exhaust and tyre-fitting garage inside was accessed through hoardings advertised with this Michelin-man made out of old tyres. Both her house and its neighbour had been bought by the Spitalfields Trust to save them from demolition, from whom my friends Todd Longstaffe Gowan and Tim Knox had already acquired the slightly more intact house to the right in this photograph. At the party which they gave to celebrate we kicked old exhaust pipes and carburetters about the wide expanses of concrete inside. Todd took this photograph in 1998. Two years later Romilly took on the house on the left, where she lives with her husband Charles Saumarez-Smith and their two sons, now grown up.

The dining room at the front of the house, with reinstated fire surround and new joinery, but the chimney breast paneling left as found.

Paint colours were chosen from Emerie and Cie in Brussels. One of a series of John Goto’s photographs of carved saints and angels from East Anglian rood screens hangs on the walls.

At her last house in Limehouse, Romilly’s workspace was a bindery. ‘I got to the end of the line with bookbinding. I’d started using metal on the books – I just loved it – I remember the first time I soldered anything – its this amazing orgasmic moment when everything heats up and starts flowing – and I really enjoyed that, so I started making jewellery, and by the time we moved in here I no longer needed a big bindery, I just needed a small room at the back,’ she says.

‘I suppose I worked for about another four years, but by the end I was struggling to make my own work and then I couldn’t do it any more, so then I had another four or five years without making, which was hellish,’ she says, alluding briefly to the illness which paralysed her. ‘But then I was given a wonderful retrospective binding exhibition at the Yale Centre for British Art, and they showed the house, and they showed some of the jewellery, and it really helped me. Being brought up as a crafts person, I was always thinking that you must make it yourself, but I understand now, that the idea is the absolute crux of the whole piece.

I started looking for someone who would help me make the work, my assistants. What has been extraordinary is that their own work is very different, but when they make for me they are being my hands, with great generosity, and I have no absolutely difficulty that these are my pieces. The difficulty is for me to try and explain what I want, but when you work with people over a couple of years you develop a language so that I can shortcut through a lot of stuff.’

‘My collection hasn’t got a name, but it is all based on things to do with the sea.’ The earrings here are inspired by drawings of seaweeds and sea wrack in a nineteenth century German compendium of natural history.

The relevant page with the earring design-prototype illustrated in the bottom right corner. The pod-like specimen above it became the necklace seen on the chimney piece in the photograph below.

‘Anna, who makes for me, draws each hole with a burr on the end of the drill – they are not cast,’ Romilly says, describing how it has been carefully hand made. Of the nacreous pendant, ‘ I wanted the feeling of a shell with water pouring out of it. Because I wasn’t trained as a jeweller, I am much freer with what I can do.’

‘These earrings fitted very well with my theme of being by by the beach. I wanted them to feel like, you know, you have a rock with mussels on it. The top bit is like mussel shells, they re very crushed together on the rock and underneath the garnets became like sea anemones, exactly that consistency of dark rather thick jelly.’

On the front landing a little closet that would have served as a wig-powdering room in the eighteenth century now houses a jeweller’s workbench.

The precious stones that she used in her latest collection were bought on ebay, they came from a manor house in the Midlands. ‘They date from about 1750 and the cuts are quite eccentric, they’re cut by hand. The seller said that they were found in a little leather bag, hidden away at the back of a cupboard.’ Only a few garnets remain unset.

‘The little diamonds I’ve used in the Reef rings and cut quite randomly, I wanted that feeling that they were growing,’ says Romilly. ‘For the big ring, you need to look through a magnifying glass, those are pearls and rough diamonds. I think it would be a nice ring for a boring dinner, you could sit and look at it and think of all those lovely tropical fish floating about. They’re not so much to do with English seas, they’re more like something you’d see with David Attenborough, with a coral reef.’

‘I bought quite a lot of garnets and then I got three or four rubies. I set them upside down, not all of them – the garnets are the right way up.’

This is an octagon cut ruby. That one, it was a dark blue sapphire and ‘tho I ‘ve worked with stones before, I was unaware of how the settings affect the stones so much, it is blue but since I set it with the other diamonds it almost becomes a dark green.’

The pinkish gold setting around this ruby ring was achieved by heating – ‘normally you would always clean up to take all that oxydisation off, but I just saw it and liked it.’

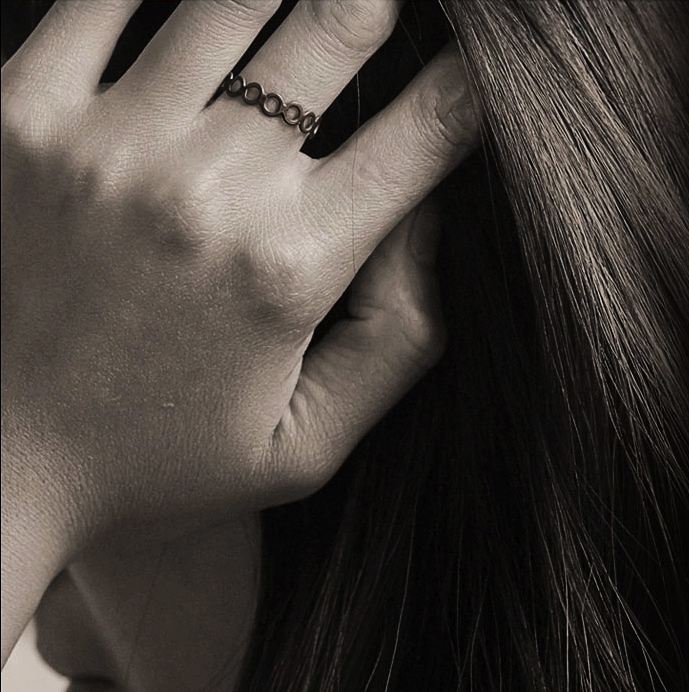

Romilly Saumarez Smith by kind permission of Lucinda Douglas-Menzies, copyright www.douglas-menzies.com/

Romilly and her work partner and friend, Lucie Gledhill have a diffusion line of jewellery using their maiden names, Savage and Chong

Savage-&-Chong – Tattoo Ring

All other photographs copyright bibleofbritishtaste.com

Lovely house, beautiful jewelry, especially the mussel earrings. I like the idea of wig-powdering closet repurposed and still in use…

Love your website!

thank you so much! r

I think Romilly’s seaweed earrings with the dangly bits and reef rings are absolutely stunning……

is there any chance at all that she may have something for sale in the not too distant future??? I see she’s recently had a selling exhibition. I would love to have something of hers, and have a birthday coming up…..

Thank you!

Jenny

I love everything about this home; decor, layout, modern aspect and especially that large opening to the beautiful back yard. Amazing!

Interior Design, A Touch Of Grey In Your Modern Home Design

Amazing space. Just beautiful.

Dear Romilly,

Lovely to see your latest sea-inspired work- and what a beautiful house you have created. I should be back in London for good this September so hope to see more!

Regards, Harriet

Fantastic house I love the sense of space and the mix of colours and textures.Can see how jewllery design is a continous flow of your creative eye.

Hello,

These photos are stunningly beautiful. Can anyone identify the EMERY and CIE purple gray wall color in the dining room? I would greatly appreciate it. Thank you

Your visit to Sue and Simon hawthorn yard interested me so I looked you up and found this website. Loved it !

I love this house, I love this blog. So interesting and refreshing to see homes that people live in and not just for show.

Just came across your website and have been up to my eyes feasting on all these wonderful articles of people, artists, homes, colours, things… can’t get enough, thank you!! Maria B