The King Penguin Guide to the Isle of Wight – a place that I once commuted to each week – was the first book by Barbara Jones that I bought. One of her illustrations shows the Horn Room at Osborne House, with Prince Albert’s Teutonic antler furniture poised as if about to scuttle across the Brussels carpet. In its pages she showed me ‘all the qualities o’ the isle,’ like Caliban in The Tempest. But some of the very best, like the ocean-going liner clipped out of topiary at Ventnor, were gone, for she had written the guide in 1950.

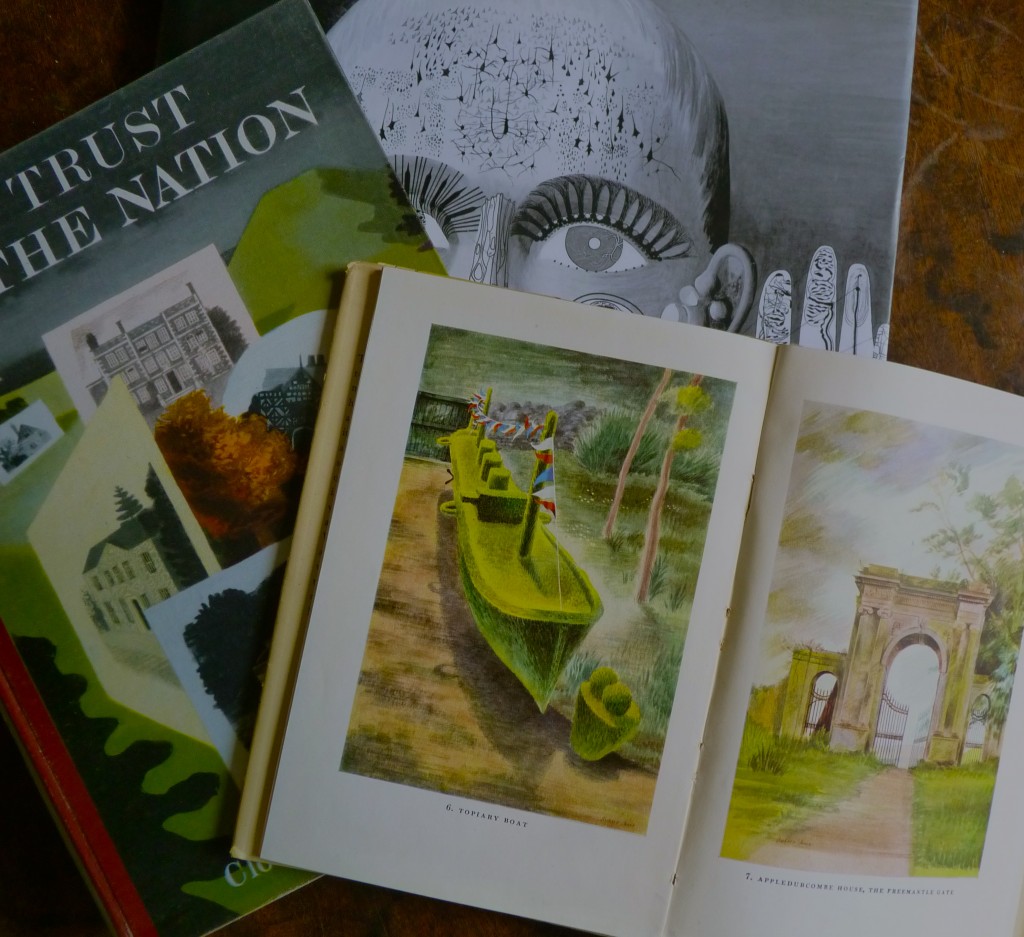

Jones’s Isle of Wight (1950), her cover design for In Trust for the Nation by Clough Williams Ellis (1947), and Ruth Artmonsky’s monograph, published in 2008.

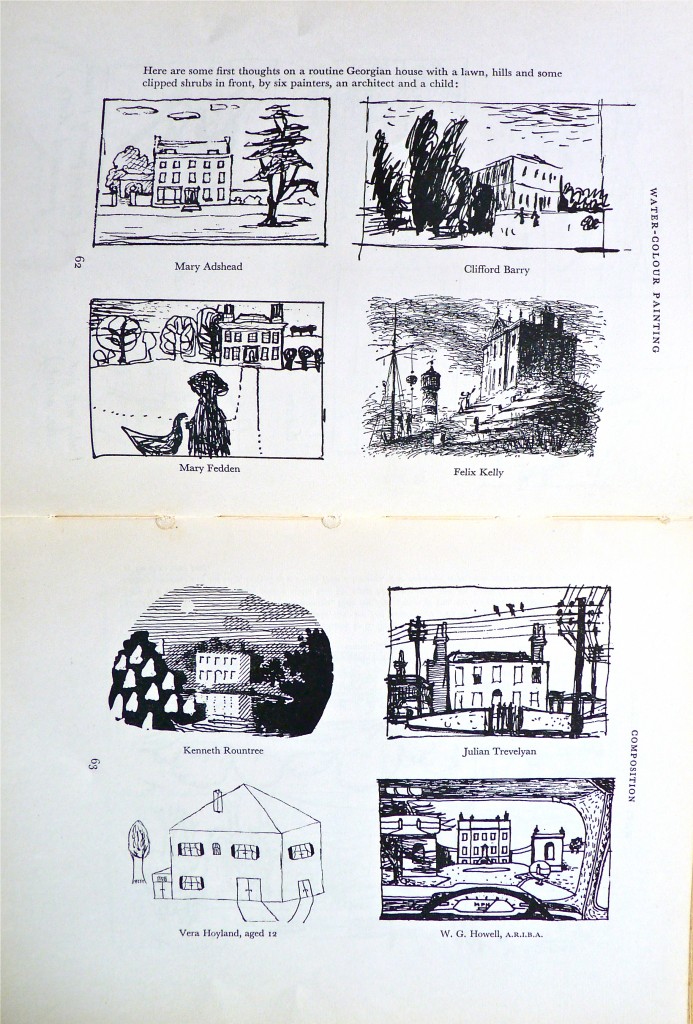

Jones’s six ways to paint a ‘routine Georgian house,’ by Mary Fedden, Julian Trevelyan, Kenneth Rowntree, Mary Adshead, Felix Kelly et al. from Water Colour Painting, (1960).

Barbara Jones died in 1978. I was half a dozen years too late, but I pursued her memory in the years that followed. Her one-time pupil Tony Raymond kindly showed me her studio just around the corner from her Victorian house in Well Walk, Hampstead.

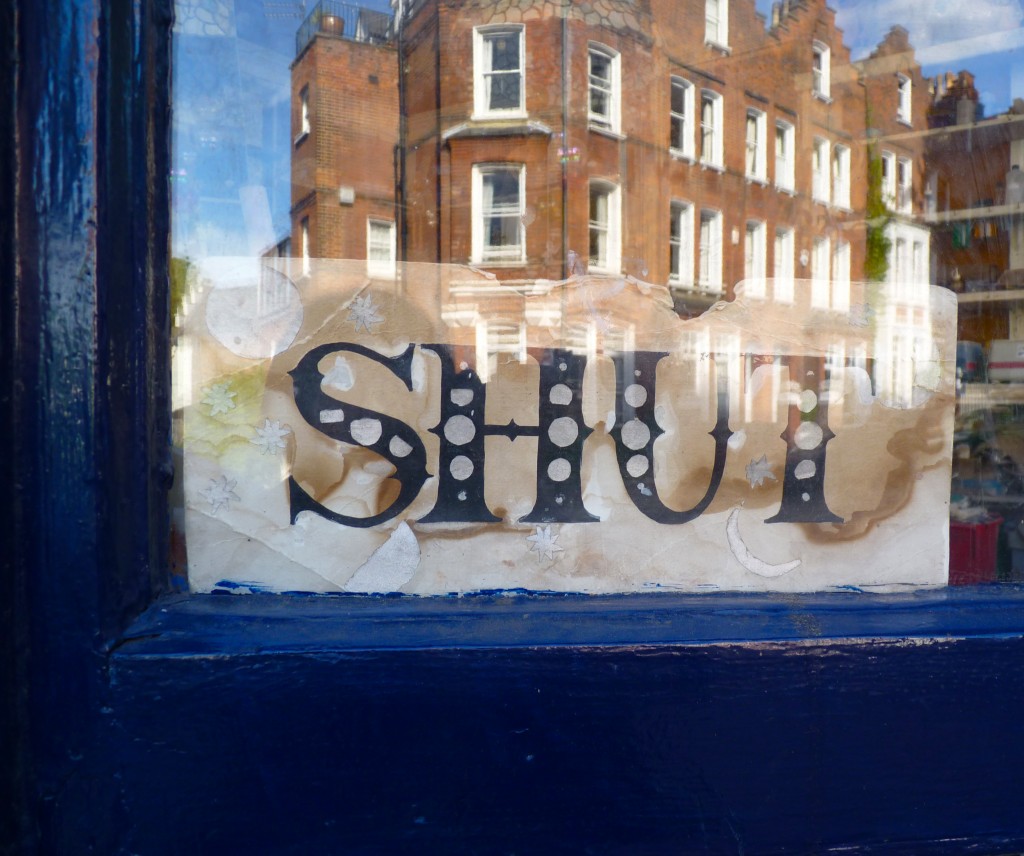

I wonder whether she drew this very beautiful SHUT sign for the pottery on the opposite corner of the street, where the shop door makes a mirror for the house where she lived?

I hung about in Crickhowell (the little town in the Usk valley where she owned a cottage with Clifford Barry whom she married and lived with intermittently), noticing what she must have seen and liked there.

I found the damp gothic gazebo at Marston Hall in Lincolnshire with her mural inside, invented for the antiquarian Squarson the Rev. Henry Croyland Thorold in the 1960s. She had painted a mysterious landscape dotted with temples and follies enshrining birds, including a penguin, but I took no photographs and that is all I remember about it.

When the Katherine House Gallery held a sale of her studio contents in 1999 we got up at dawn to be first when the doors opened.

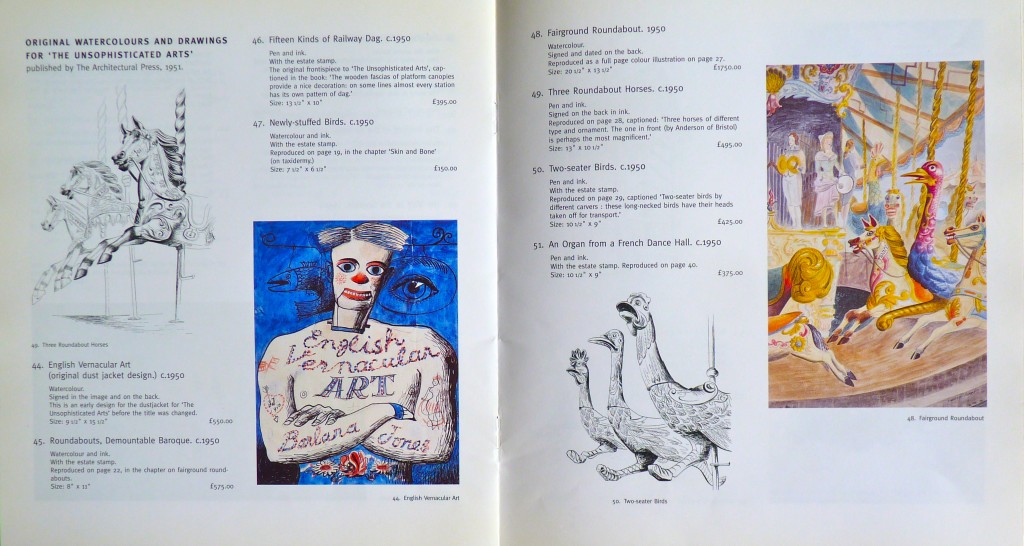

Unknown to us the gallery had been selling over the telephone and everything that we wanted had a red dot, but £50 bought me ‘Photographer’s background,’ her little sketch from The Unsophisticated Arts.

This became my favourite of all her books. There is a chapter on roundabouts – ‘Demountable Baroque’ – and the first of its plates is of taxidermists preparing a record-breaking Tunny fish for preservation.

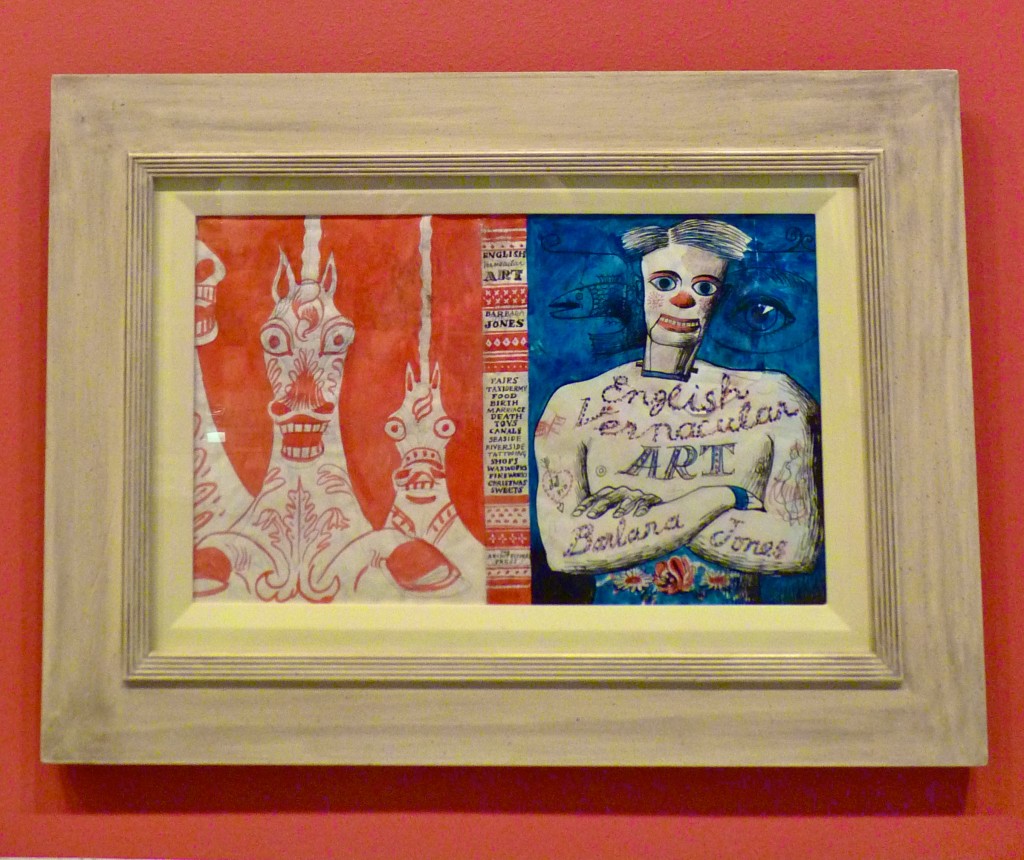

The Unsophisticated Arts, original artwork for bookjacket by Barbara Jones, 1951, a tattoed ventriloquist’s doll-cum-wrestler juxtaposed with merry-go-round prancers.

Then a year ago in the foyer of Cecil Sharp House I saw this:

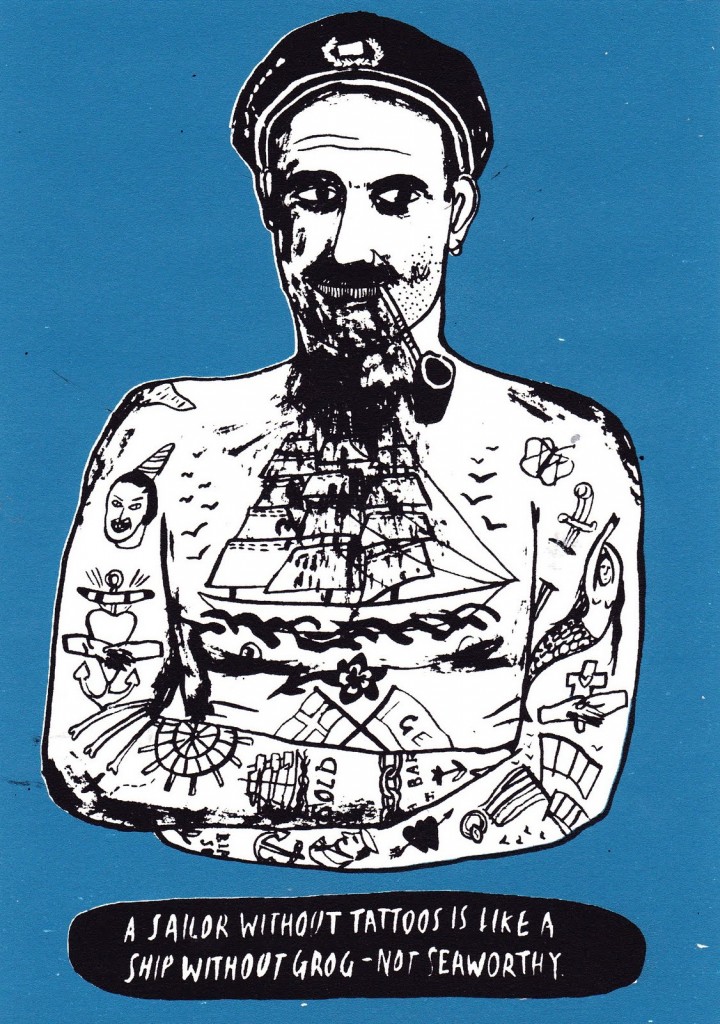

Sailorman by Alice Pattullo.

The print was for sale for about £30 and I bought one. When I met Alice a few weeks later I asked if her sailorman was a kind of homage to Barbara Jones’s tattoed book-cover man, and she said,’ Oh, Barbara Jones! I think my life is a homage to her!’ and I was smitten.

Barbara Jones was interested in almost everything, taxidermy, tattoeing, shop signs, toys, advertising, labels and packets, shellwork, folk art, buildings and landscapes, but perhaps not so much in people. She could have read English at Oxford instead of going to art school and her friendships were often with those who had – Rose Macaulay, author of The Towers of Trebizond, whose London novel The World my Wilderness has an evocative book jacket by Barbara Jones. Jones’s little sketches and cartoons were very like those of the poet Stevie Smith, whom I feel sure that she must also have met. All three were hobbled by living in a pre-feminist world and wary of making too many compromises with it. Jones made Pop Art before the term had been invented. Her contemporaries and her peers on the Recording Britain project in wartime included Kenneth Rowntree, Eric Ravilious, John Piper and Edward Bawden but she remains far less well known.

Perhaps this is because of the anti-chocolate box bias in her way of seeing, her preference for the incongruous, mundane or even downright ugly over the straightforwardly picturesque or felicitous. She was clever and easily bored and inclined to play things for laughs and never wanted to specialise in one thing for too long.

Poster designs for Black Eyes and Lemonade, Jones’s 1951 exhibition of popular art and design at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Rather than go on, I will just recommend the Whitechapel Art Gallery to you, where in a single room and a very small way the exhibition Black Eyes and Lemonade pays tribute to Barbara Jones until September 1. The essay published to go with it, Barbara Jones and the Art of Arrangement by Catherine Moriarty is a good one and if you ask they will give you a copy. The show, guest curated by Simon Costin, looks back at the grander, more eclectic one which Jones staged there in 1951. Jones had ended her catalogue essay then by suggesting that the V and A should acquire a ‘whole glittering roundabout.’ As far as I know they never have, but when I saw the dusty ears of a Victorian fairground horse poking up behind armoires and tables in antiquaire Malcolm Glickstein’s shop last year I felt giddy and reckless. I had been filled with regret ever since the fairground goat which I had coveted there turned up in the Museum of Everything’s exhibition no.3, lent by Peter Blake, who had described Jones as ‘one of the more important things that happened to me.’

Now that this horse is a few feet away, blocking my study window, I realise that the image that flashed into my mind when I saw it was this one, Jones’s School Print lithograph Fairground, a Proustian scene that I have been trying to revisit ever since.

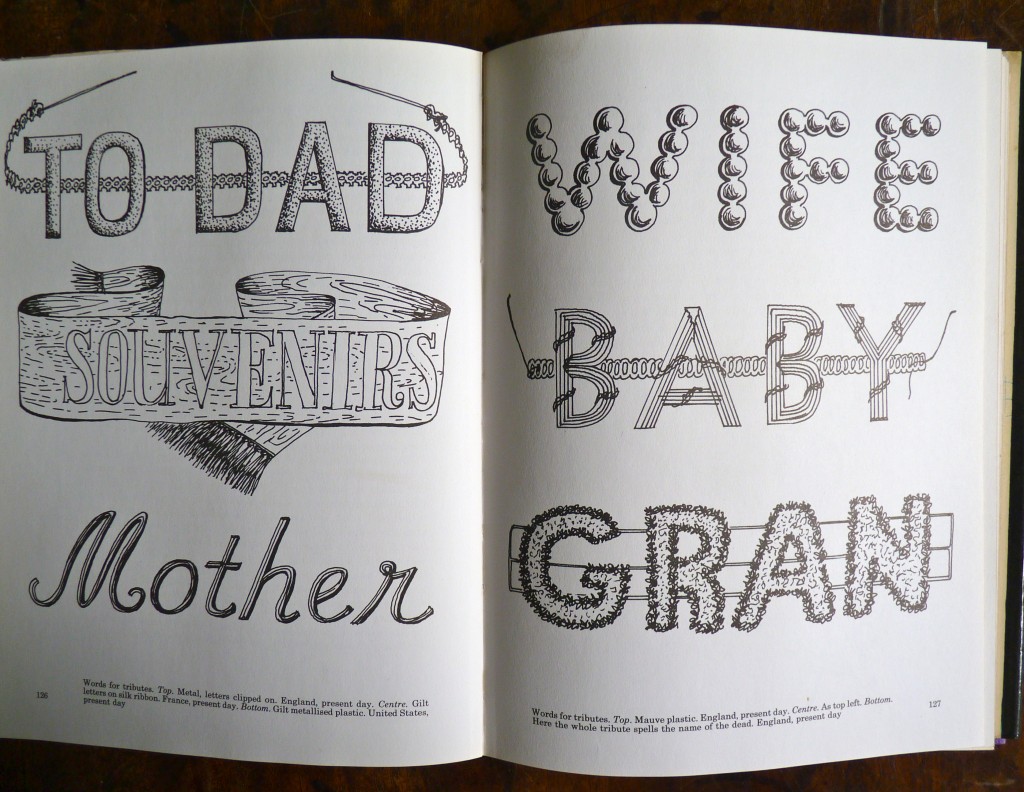

Jones had a fairground galloper’s head that she named ‘Nora ’ which can be seen at the Whitechapel. Otherwise this show scrimps on its exhibits – justice requires a larger budget and a freer hand. Jones had installed ship’s figureheads in her 1951 exhibition, pub signs and mirrors and a live pavement artist lured from his regular pitch outside the British Museum. A collector herself, she was well aware that the ‘common’ things of ‘nowadays’ would be the antiques and museum pieces of the future : Their steady ritual progress will follow clearly ordained lines; via the appreciation of the common man into almost total oblivion, out again to the intellectual home, onward to the antique shops and finally to permanent deification in wealthy drawing rooms and museums, she wrote.

But this gigantic optician’s sign recreated at Whitechapel by Simon Costin is a good touch, commemorating the one that Jones had borrowed from the Croydon shopfront near her own father’s saddlery business.

Her watercolour of the shop from which it came is one of the plates in The Unsophisticated Arts. It was item 58 in the sale of her studio contents in 1999. I regret that I do not own it to this day.

Yet again a lovely insight into someone’s world. And Jones’ world is captivating. Thank you!

Ruth this is the best blog yet. I know i say that every week. B xxx

New found love: Bible of British Taste.

Just discovered this…………………….Very best of the best!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

wonderful to see such a well-informed piece about Barbara Jones. I too went to the Marlborough Gallery. I managed to buy a few things but so much had gone, and others beyond my means.

You might be interested in a project I’m self-publishing about Noel Carrington who commissioned BJ for a number of quite stunning greetings cards for Riyle Publications. Noel was also responsible for the Puffin Picture Books, as well as commissioning Ravilious for High Street, and was an early champion of English Popular Art.

There’s more on a website I’ve put up about the project at

http://www.designfortoday.co.uk

regards

Joe Pearson

Great post – have shared on my illustrations page too Thanks for all the images! x

i was just wishing that i wanted to find a website like yours about cool and obscure british stuff.

just as i formulated this wish up came your website.

i was reading the tls about barbara jones the unsophisticated arts and after i googled her you were there amongst her articles.

wish i had seen this exhibition…..

Wonderful blog post, at last some insight into this very talented and ripped off artist.. er hem ‘homage’ indeed!

Thank you for such a great post. I just wanted to point out that the exhibition was jointly curated by myself, Catherine Moriarty, Curatorial Director of the University of Brighton Design Archives and Nayia Yiakoumaki, Archive curator at Whitechapel Gallery. Glad you enjoyed it!