Quinlan Terry is a deeply serious proselytiser for classical architecture.

His traditional practice – operating outside the mainstream architectural establishment – has gained him many plaudits and the occasional brickbat.

Half-hidden by a Wellingtonia, the house with its Georgian facade, into which Quinlan and Christine Terry moved with their four children in 1980. The classical facade disguises a much older house of red brick. Inside everything is in accord, harmonious and all of a piece and nothing is superfluous – this house has a poetic completeness.

Christine Terry was born in Poland in the year in which war broke out and came to England on finishing her Baccalaureate at the age of 16, to train at the AA [Architectural Association] where she and Quinlan Terry met. ‘ I never really liked the Modern. I knew about the classical orders and how to put washes on watercolours, and Quin rather employed me to help him do a classical scheme.’

Upstairs and downstairs, there is exquisite trompe l’oeil painting rather than colour or wallpapers, in historicising designs appropriate to the decorum of the various rooms. Each panel was first drawn up at the office, then glued to the wall and painted in situ by Christine.

Their daughter Martha’s bedroom. Francis [their son Francis Terry] painted the rustic scenes in the middle of each panel, inspired by designs from toile de joie.

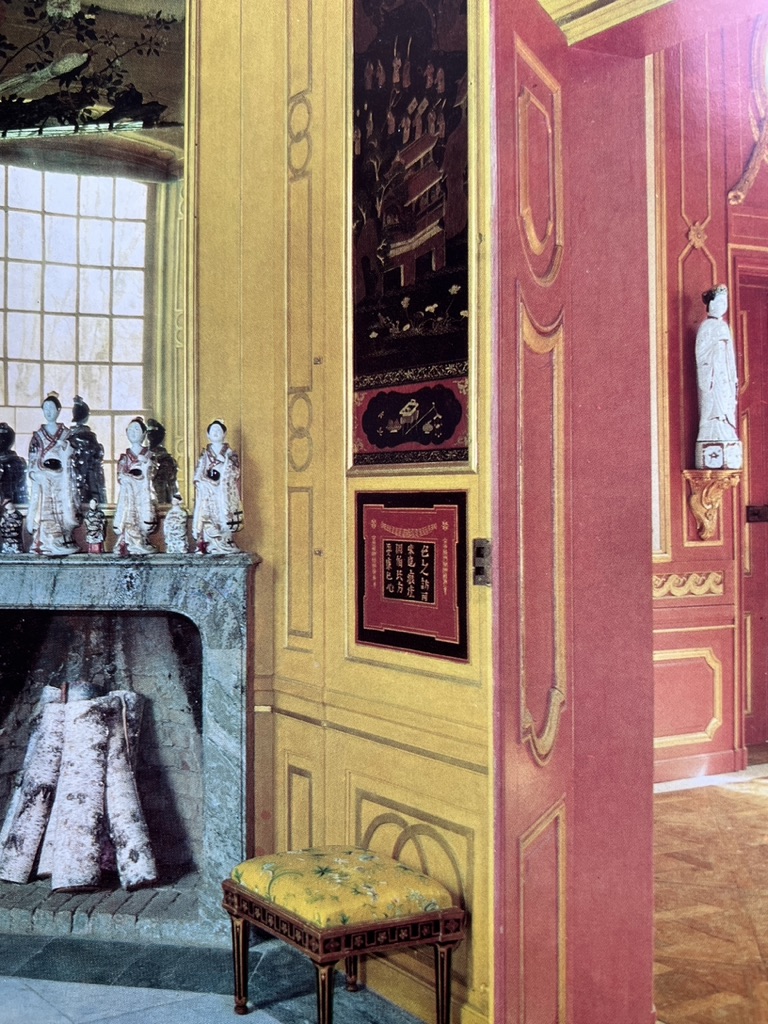

The overall inspiration was the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm Palace in Sweden, based on drawings by the English architect William Chambers (who was born in Sweden to a Swedish mother).

The view in the cartouche is the one from the window of the Master Bedroom

Martha’s childhood bedroom, she immediately covered it with pictures and college photographs..

The guest bedroom next door was painted by Christine Terry too.

Its yellow colour is based on Drottningholm…

Chinese Imperial Yellow.

Faux masonry, ashlar blocks painted throughout the entrance hall and ground floor corridors, the effect perfectly achieved with a T-square and lines of white paint over which a pencil is run.

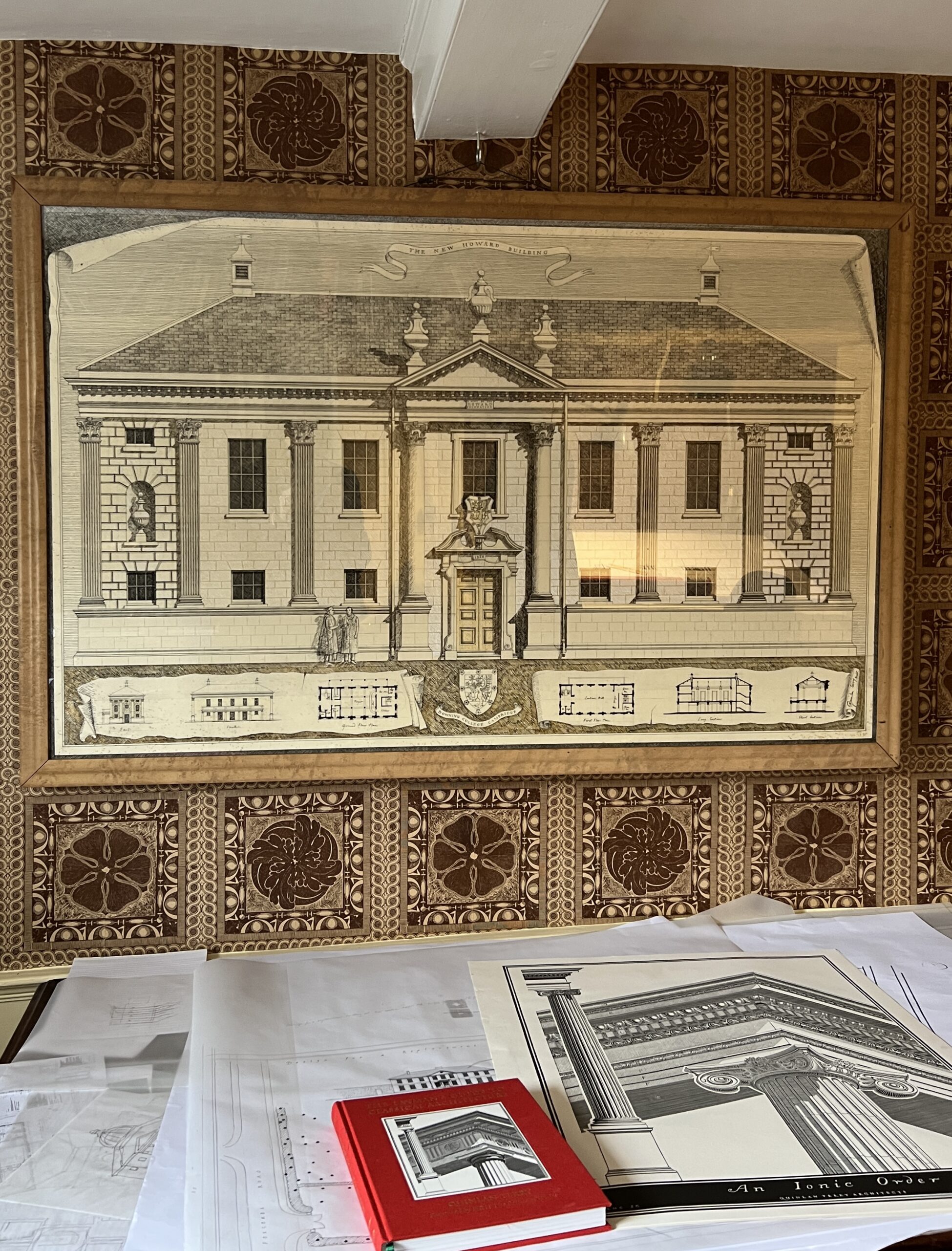

Quinlan Terry’s study. The house – ‘We ‘ve been there for a long time and it’s like everything else, you buy a bit of furniture you do things as you go along,’ he says.

After a pause – ‘It helps having a nice wife, that’s the key to it all I think.’

‘The support of Roger Scruton and Prof. David Watkin came at a very important time, because there weren’t many people standing up for us. This is how Scruton put it in a piece he wrote about my work in The Spectator, April 8th 2006, he said – Quinlan Terry converted to Christianity which taught him to question all the self-serving dogmas on which he had been raised, including the dogma of Christianity… ‘

Model of the Tower of the Winds, awarded for Contributions to Classical Architecture, 2015.

Staircase hall, Piranesi and pram.

Architectural drawings lining the spine corridor

The Doric Order in the kitchen

In both the Kitchen and the Drawing Room, classical orders were drawn onto tracing paper, printed and then stuck up and painted in situ

‘The columns weer begun by Quinlan Terry and completed by Francis [Terry] with the assistance of someone from the office.

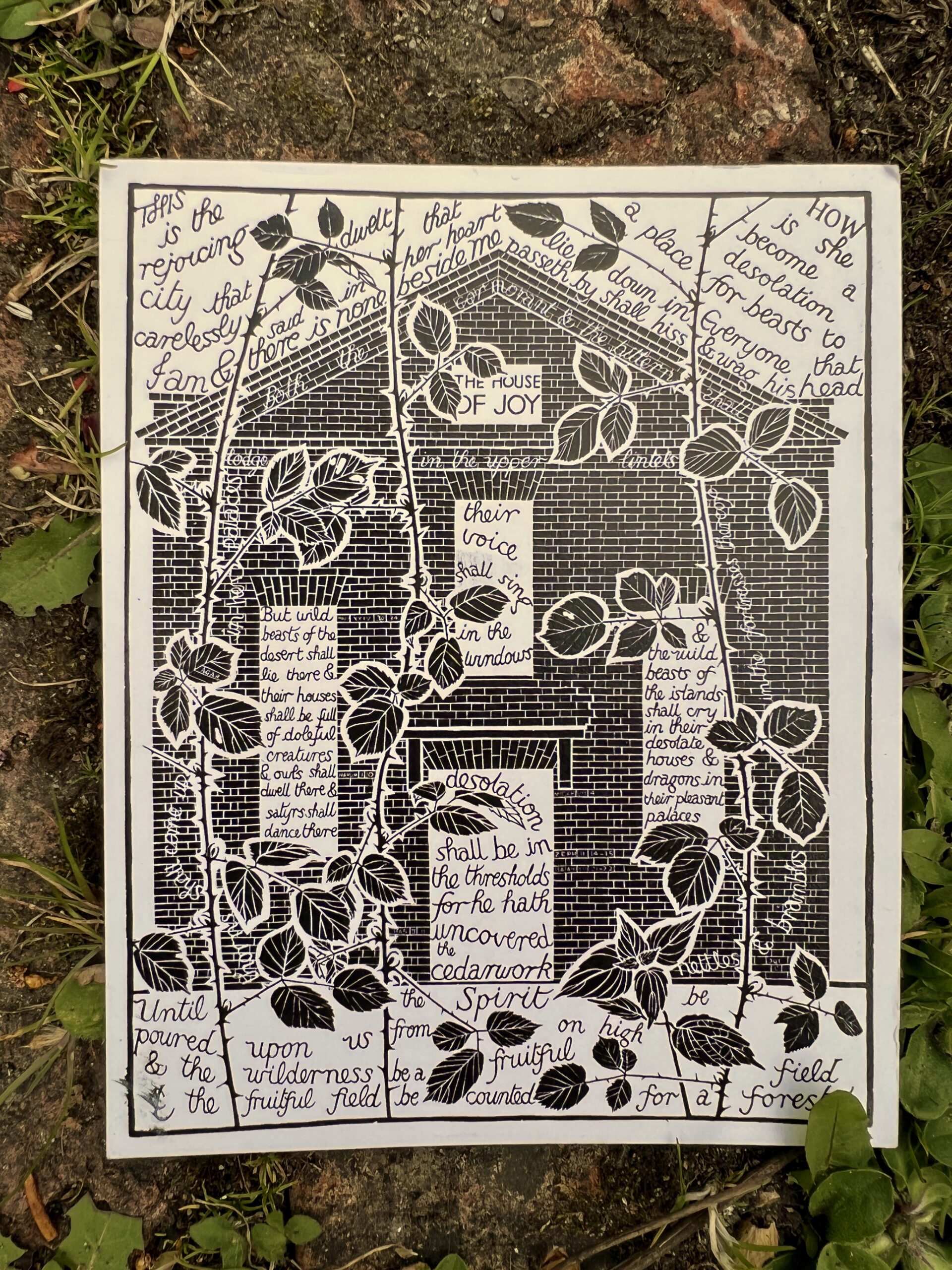

The kitchen is hung with linocuts by Andrew Anderson who was Q.T.’s student colleague at the AA and several of his own architectural designs, most notably, Fantasy of the House of Joy, a highly charged, symbolic image of a derelict Nonconformist chapel created during 1960, Quinlan Terry’s exeat in Oxford from studying a Modernist curriculum that he was coming to detest. ‘I thought the demise of that sort of church and the demise of classical architecture were bound together.’

He drew the chapel’s brick façade overlaid with a pattern of brambles and nettles and lettered with dolorous quotations from minor prophets in the King James’ Bible, and printed it on an Albion Press. It was his protest against the destructiveness, pride and spiritual barrenness that he had found in contemporary and professional life. ‘Sadly the original linocut of The House of Joy , which was mounted on blockboard, became part of a raft for Francis to use in our pond, many years ago. So I can only copy from the print…’ Quinlan Terry wrote a few years ago when I had hoped to buy one.

Kitchen and pantry

There are 3 kitchen dressers… !

The Aga is used every day

major dresser

The Pompeiian red dining room, decorated in red ochre and size, a scheme devised and executed by Christine Terry.

Pearwood-carved representations of the orders, commissioned by Quinlan Terry and made with interchangeable bases

Murano glass chandelier, that fell to earth but was repaired with new branches sent from Murano.

The source book …

The marbling was created by a ‘wonderful ‘Australian au pair, ‘she was a nanny, a groom, a cook, very artistic, she was anything you like!’

The frieze was added by Quinlan

One of a pair of Baroque church vestry paintings that Quinlan and Christine bought in in London representing episodes from the life of St. Paul

Looking into the Drawing Room

When they arrived in 1980 this room was a ‘hideous ‘pink colour. Quinlan immediately began painting a section of the frieze and wrote up the words , Dominus Regnavit, taken from Psalm 97, below the cornice.

‘It’s a fag doing trompe l’oeil. You do it for yourself, you make all sorts of mistakes, but you can live with them. This room was a horrible colour and we painted it out. It was quite helpful having those Sapota figures, those various gents standing up. I wanted some figures and I’m not very good at drawing figures, so I lined up – Raymond Erith had a book on Giacomo Serpota – so all those figures are actually taken from him,’ says Quinlan.

The effect was achieved with just two tones of grey and one white.

Neoclassical marble statuette of Paris

down the Drawing Room

The second of their pair of Italian church vestry paintings, St. Paul arrives in Rome from Ostia.

old varnish and patina

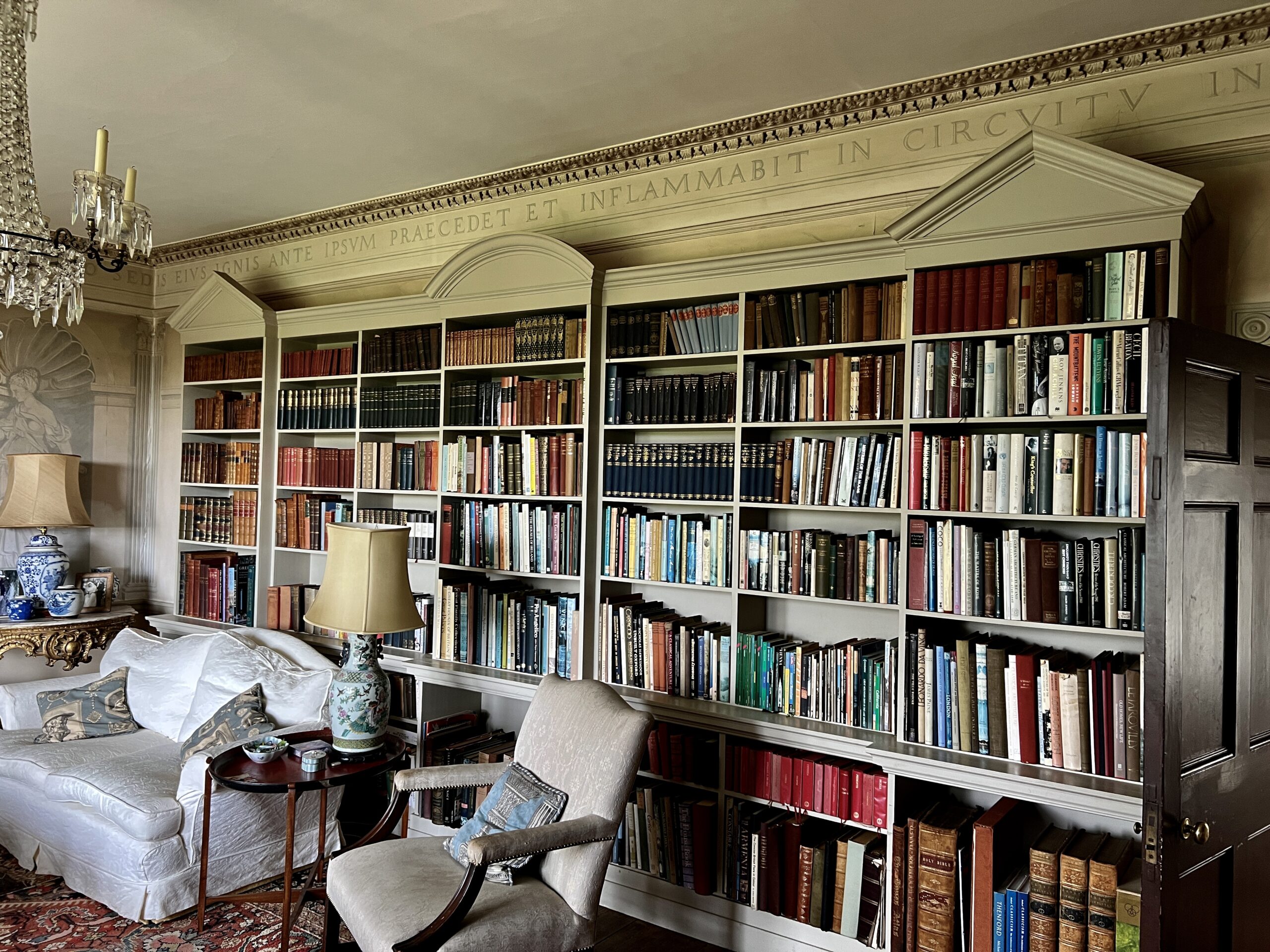

Neoclassical bookcase

upstairs landing looking into the Master Bedroom, NB, ashlar.

‘Francis designed their bed – the back and the baldacchino top – around a set of antique bed posts. A ‘wonderful lady’ did the upholstery.

Quinlan began started painting the room but then stopped when a baby was born, the room remains unfinished.

There is a lot of Tudor brickwork in the house…

‘that dark brick is the Tudor brick.’

This bay window was put in at about the same time as the front of the house was refaced.

One man went to mow. Topiary running down to the river decreases in height to create the illusion of a much longer vista.

Landing and cupola-skylight, portrait by Francis Terry.

long, long spine corridor – the Nursery is at this end…

And in many ways the most spectacular room of all – because its fantastical theme after Lewis Caroll and Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice in Wonderland is so wholly unexpected. Francis Terry was 15 when he did this for his little sisters , Martha and Sophie, in the 1980s, Martha was 5 ,…

All done in watercolour…

Mad Hatter

[‘You’re nothing but a ack of cards!’ cries Alice at this point in the story…]

Flamingo-croquet

Christine loves lying on this bed and looking at the Cheshire Cat…

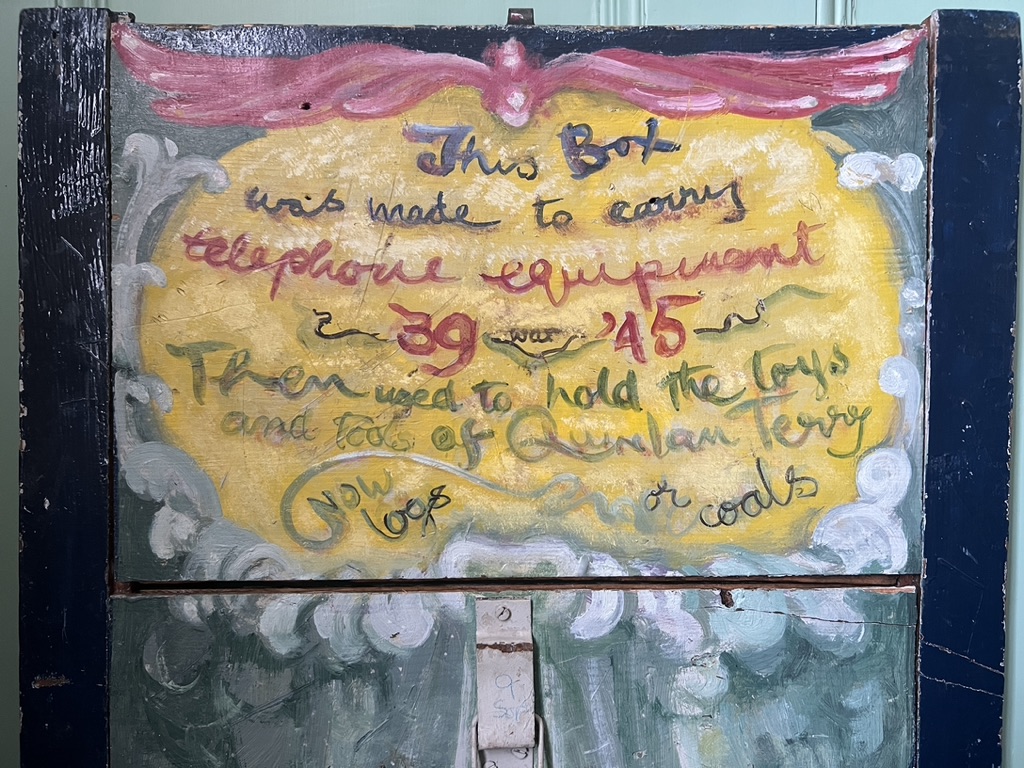

The painted box in the nursery was a box that had held an army telephone – Quinlan’s toy box painted by his mother who was an artist.

Quinlan’s mother and father were friends with Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicolson, his mother used to babysit the Hepworth triplets before she had her own children.

The legend painted by his mother inside the toy-box lid, which next did service as a log-box.

Cheshire Cat, grinning…

The Old Exchange, Raymond Erith’s architectural practice housed in a pair of Elizabethan cottages at one end of Dedham high street, on the Essex-Suffolk border. It has the quiet, settled quality conjured by J.R.R. Tolkien for his fictionalised ‘Shire’ in Middle Earth. Quinlan Terry began working here for Erith in the 60s, eventually taking over the practice. ‘Christine and I were both working in John Brandon-Jones’s office, he worked in Hampstead, we lived in Hampstead – [J B-J was a SPAB stalwart, a founder of the Victorian Society and a living link with the Arts and Crafts movement]. ‘He was a sort of supporter of those who weren’t modernistic, he wrote to Erith and said, ‘Be nice if you could interview QT?’ – and I came here in 1961 and we got on right from the moment we met. Erith offered me a job, but on half the salary I was getting in London. Erith was working on the Downing Street commission then and Christine worked here in this office too, helping with Downing Street, ‘ says Quiinlan.

On the AA and meeting Christine: ‘I got the Natural Asphalt and Muck Spreaders Association scholarship to the AA from my school, there were 3 going. The top scholarship was the Leverhulme scholarship, and Andrew Anderson got that and Malcolm Higgs got the second. Somehow we were sitting pretty close to each other, Andrew was on the next board. Andrew was outstandingly gifted, he could do linocuts like nobody else, lettering, he was brilliant at, and he had a stammer and he was a very interesting chap. Christine came in speaking some unknown language, this incomprehensible language she was speaking was intriguing to us. We went to Rome for 6 months because I was a Rome scholar, I was going through these Teach Yourself classes trying to learn Italian and she pretty much ignored all that, but when we got to Italy she was the one speaking Italian!’

‘My parents were sort of left-wing by profession, typical NW3, Hampstead, they didn’t believe a thing. I think really the big change came in the first year at the AA you know. I told Andrew Anderson that I went to an Anglican church just to see what they were talking about, and he said – Oh you want to come to the Westminster Chapel – it was a Free Church, technically Congregational. Andrew shared this faith with me and at one time there were about 8 of us going there from the AA. Christine was brought up a Roman Catholic and quite sincere, and she was half way there already, Andrew and I were sort of inseparable buddies then, we used to go hitch hiking together. We were called the Flower Pot Group rather uncharitably by some of the others, we stood against Modernism and were not to be taken seriously.’

‘Later, I went back to work at Downing Street and that was rather pleasing. I really wanted Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders on all the fireplaces as each floor ascended up through the house and quite an ornamental ceiling. I designed it all and then English Heritage recommended that it wasn’t carried out. So, Margaret Thatcher told me – ‘But I thanked them for their advice – and I didn’t take it!’ She was a very appreciative client and encouraging to the men who did the work.’

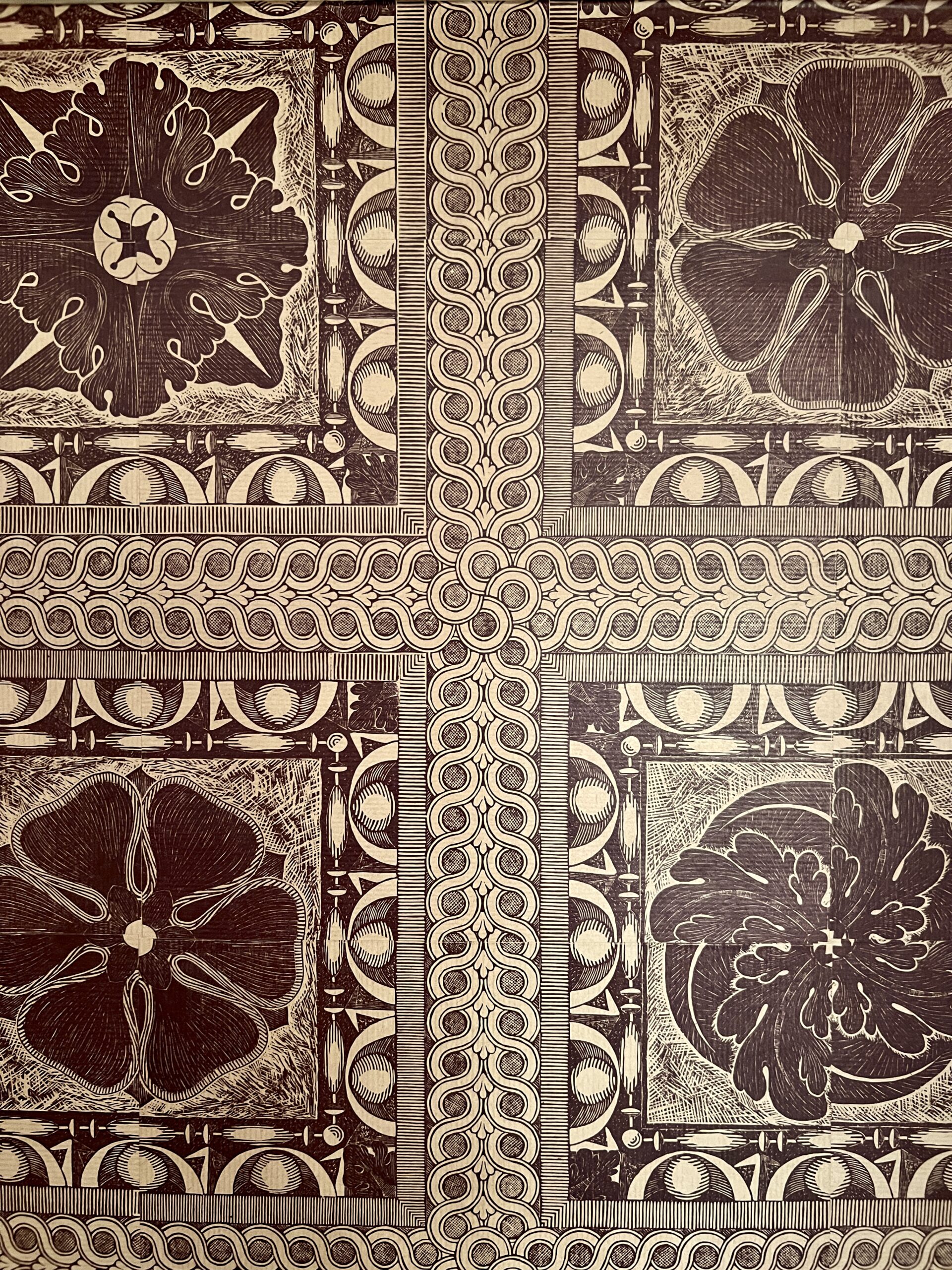

‘The newspaper that lined this office’s walls was originally put up by Erith – but it got so messy that I put these linocuts up. I’d learned lino-cutting at school. I did this design in the late 60s. You’d think that it has 4 different flowers and therefore there’s four different linocuts, in fact it’s just that – one. So in fact you could buy the linocut print – its exactly 12 x 12 inches – and just turn it round, reprint them and stick them onto the wall.’

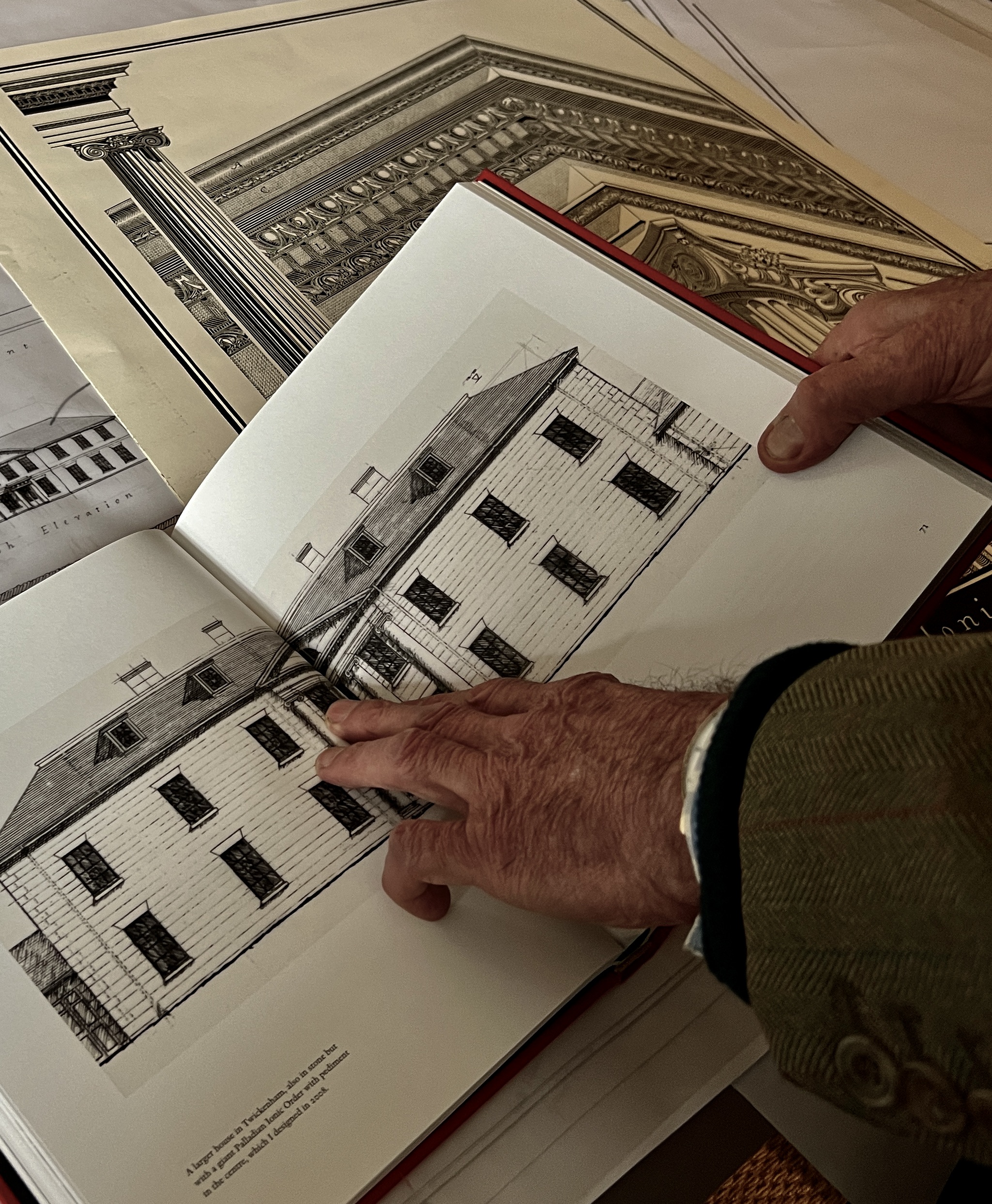

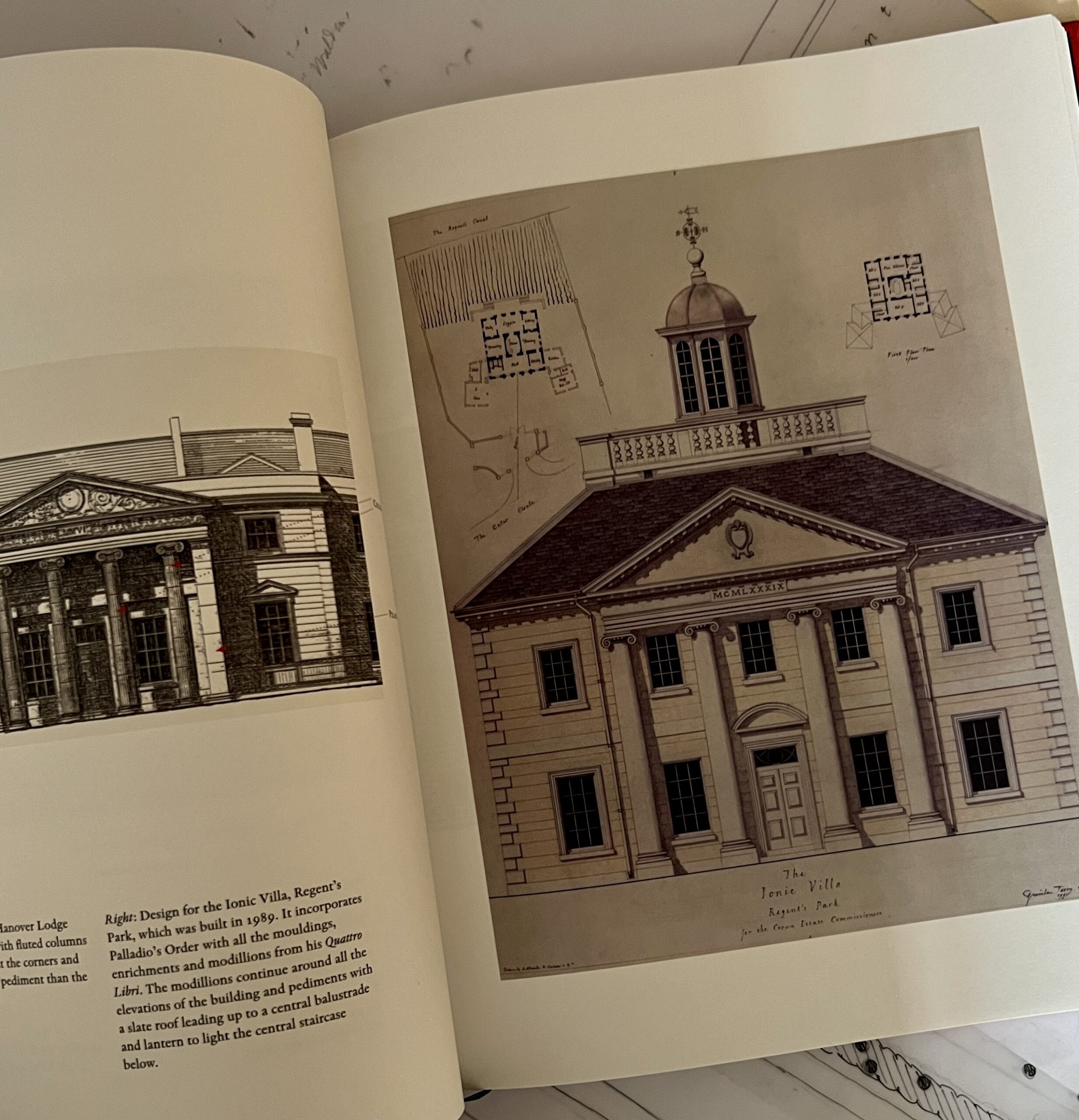

Quinlan Terry’s practice has built many new country houses, a chunk of the Prince of Wales’s model village at Poundbury, a Roman Catholic Cathedral at Brentwood, a Library for Downing College Cambridge and a row of picturesque villas for the Crown Estate along the bank of the Regents Canal in London : ‘Building a castle for the Barclay brothers on Brecqhou in the Channel Islands was a very interesting job. The house was all of granite, the only castle I’ve built. Barclay approached me, he’d always liked classical architecture and he’d always liked gothic, and he saw the gothic villa I’d built in Regents Park and thought that’s the sort of house he’d like. We had lunch at the Ritz or somewhere and he said, I know what I want, and he had it on a piece of paper. I drew it up and he said, Yes, that’s what he wanted, and we didn’t have to get planning permission but I did have to go and see the Seigneur of Sark.’

Quinlan Terry’s new book , The Layman’s Guide to Classical Architecture, edited by Clive Aslet, was written during the pandemic when two lectures that he was to have given then were cancelled. ‘The key is in the book,’ he says, ‘It’s a textbook teaching people, which is dull for most people but for someone who really decides to interest themselves in architecture it would be useful. People won’t understand classical architecture unless you explain to them what the parts are and what the details and names are, it’s like wild flowers, unless you know the parts, sepal and stamen, you don’t understand botany.’

Beneath it is the linocut that appears on the cover by Eric Cartwright, partner at Quinlan Terry Architects and a Brother of the Art Worker’s Guild, prints of which can be purchased here

The book

Quinlan Terry, (his suits are ’years old’ tweeds from his tailors Welsh and Jeffries.) – ‘This was the Bahai temple in Tehran, it was my drawing. I said, When will it be built? and they said, When we are allowed to. It was the last thing I did with Raymond Erith, he died when it began. They were paying us to do all the drawings until such a time as they got permission. And it was never built.’

For Terry the classical tradition in architecture and its five orders are God given and so it would be fundamentally wrong to challenge them. ‘You just want to understand the tradition and do it well,’ he says. ‘ The highest complement any one can give me is to say, it looks as though its always been there.’

Very many thanks to Christine and Quinlan Terry and Eric Cartwright. All photographs copyright bibleofbritishtaste. Excerpts may be used as long as clear links are supplied back to the original authors and content.

The Layman’s Guide to Classical Architecture by Quinlan Terry.

I am speechless; such ordered beauty ! Thank you for lifting my Friday afternoon spirits.

Lovely – I sneak in to your website now and then to se if there is something new. This was a great treat after doing the “office work” on a Saturday. Thank you again <3 C

Astonishing post! Thank you.