John Betjeman hated experts, antiquarianism, art historians and research fellowships. As his daughter Candida Lycett Green has pointed out, he never set out to champion conservation in the academic sense of that word, but rather to work in the cause of what he called ‘indeterminate beauty,’ a quality invariably left out of official lists and heritage campaigns because it is impossible to define.

Betjeman’s poetry is full of myriad contradictions, and coloured by the preoccupations that made up his character, lust mingled with piety, topography, architecture, churches and communal hymn singing, hilarity, knowledge and high seriousness. After a youthful dalliance with snobbery he went on to develop a gift for finding beauty in the mundane and ordinary, and by 1940 he was professing his deep love of suburbs and Gothic revival churches, provincial towns and garden cities and all kinds of things unchampioned and derided by the taste-makers of the day. As he pointed out, ‘they are part of my background.’

It was this appreciation for the legacies of his middle class upbringing that went to make him such a sympathetic figure, someone whose imagery, humour and understanding chimed with thousands of others, the eager audience for his books and journalism and television broadcasting after the war which was to destroy so much of what they were used to.

An Oxford University Chest, John Betjeman, (London, 1938), illustrated with photographs by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and caricatures by Betjeman’s friend, Osbert Lancaster. These pages are captioned ‘Bullingdon’ and ‘After Hall.’

It was written a decade after Betjeman had been sacked from Magdalene College, Oxford, a victim of his bullying tutor C.S. Lewis, who despised JB as budding aesthete with a lack of seriousness. Betjeman described Moholy Nagy as, ‘ a huge man with a constant smile and shaped like a large, oval water beetle which suddenly comes to the surface and dives out of sight. Moholy had a Leica and rushed about frenziedly photographing everything he saw.’

Although his poetry was and is still widely read, he is now probably even more famous for his stance as a conservationist, campaigning for a range of buildings that many then considered to be unimportant or ordinary or even hideous. As Timothy Mowl has written, his achievement was to go ‘at least half way to converting a philistine nation to something which it then christened ‘heritage’ and half destroyed.’

His efforts in the 1930s and after the war, and those of others like him, are celebrated in English Heritage’s new free exhibition in the Quadriga Gallery of the Wellington Arch at Hyde Park Corner, Pride and Prejudice: The Battle for Betjeman’s Britain, from 17 July – 15 September.

Betjeman’s love of the Church of England percolates through his poetry and writing, showing modern Englishmen and women how to love their churches and their Church. The relics and objects that he collected throughout his life were emblems of these deeply held tastes and beliefs.

St. Mary’s Church Penzance, model encrusted with shells by an unknown maker, later furnished by Osbert Lancaster, with a gothic organ loft and a painted glass window at the west end.

In A Passion for Churches, filmed for the BBC in 1974, Betjeman says in his commentary, ‘A church should pray of itself with its architecture,’/… But there’s another way./ At his ordination/ Every Anglican priest promises to say/ Morning and Evening Prayer, daily./ The Vicar of Florden/ Has rung the bell for Matins/ Each day for the past eleven years./ It doesn’t matter that there’s no one there/ It doesn’t matter when they do not come/ The villagers know the parson is praying for them in their church.’

But earlier in his life, after he parted from Nonconfomism, he invested his childhood teddy bear, Archibald Ormsby-Gore with an almost fundamentalist passion for Nonconformist worship of the lowest and plainest kind.

The bear Archibald Ormsby-Gore and his dimmer friend Jumbo, seen here back at home in the Vale of Uffington, propped against a painting of St. Enodoc’s, the Cornish church-next-the-sea where Betjeman lies buried.

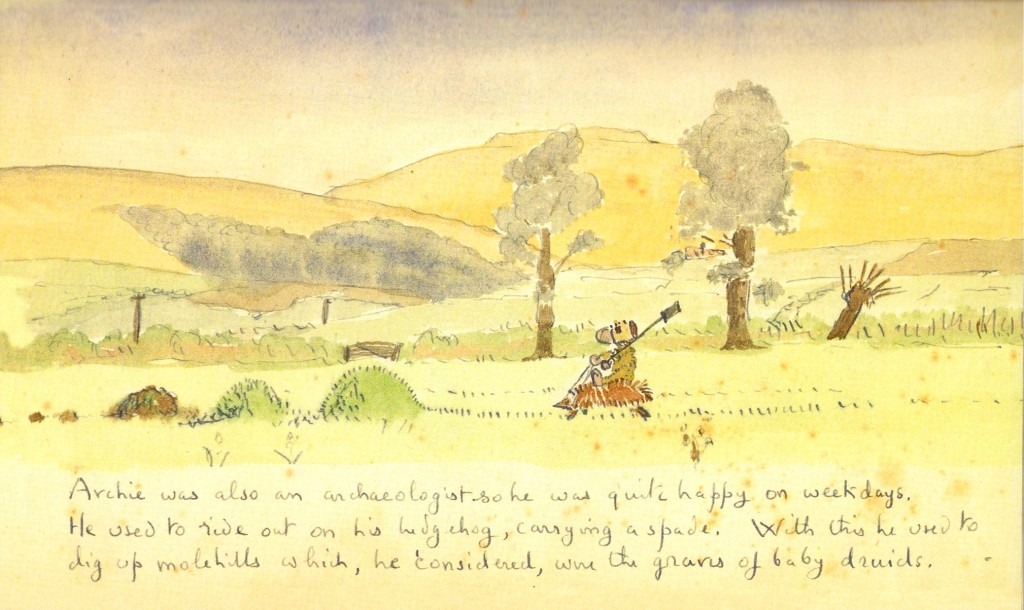

Archie’s fervour is evidenced in the story book, Archie and the Strict Baptists, that JB drew and wrote for his children, republished in 2006 by Long Barn Books.

Archie eventually cut a pair of wings out of brown paper to fly, Icarus-like, over the fields to a chapel where his preferred creed of Strict Baptist was on offer.

The rest of the time, Archie was an amateur archaeologist who set out on hedgehog back to excavate the mole hills around the Vale of the White Horse in Uffington, which he believed to be the funeral mounds of ‘baby druids.’

Betjeman’s antiquarianism and huge knowledge of architecture and topography were shared by his kindred spirit and friend John Piper. Together they collaborated on the Shell County Guides, and post-war, three more architectural guides for Murray’s publishing house, a series that was discontinued as the Shell Guides were revived.

Betjeman was the author of the Shell Guide to Cornwall, ( 1934), revised in 1964, the surrealist collage for the cover of Wiltshire (1935), is by Lord Berners.

His daughter Candida Lycett Green has followed the same paths and shares many of her father’s strongest tastes. She is the guardian of the bear Archie and his friend Jumbo; JB died with these two childhood toys resting in the crooks of his arms. She is the editor of her father’s letters and prose and the author of Unwrecked England, a column which she has written for The Oldie magazine since 1992; her latest book is Seaside Resorts (2011), and you can follow her on twitter.

She is also a skilled horsewoman, novelist, stylist and contributing editor to Vogue. Nicky Haslam described her as the living person he most admired – ‘beautiful, brave, strong, clever, loving and loved.’

Here she is with with her husband Rupert Lycett Green, co-hosting one of their famously good parties on a boiling Sunday in May .

Candida and her family run a poetry competition for 10 to 13 year olds (‘Childhood is measured out by sounds and smells and sights,/ before the dark hour of reason grows.’ John Betjeman, Summoned by Bells’) www.betjemanpoetrycompetition.com

Each year it awards a generous prize of £1,000.

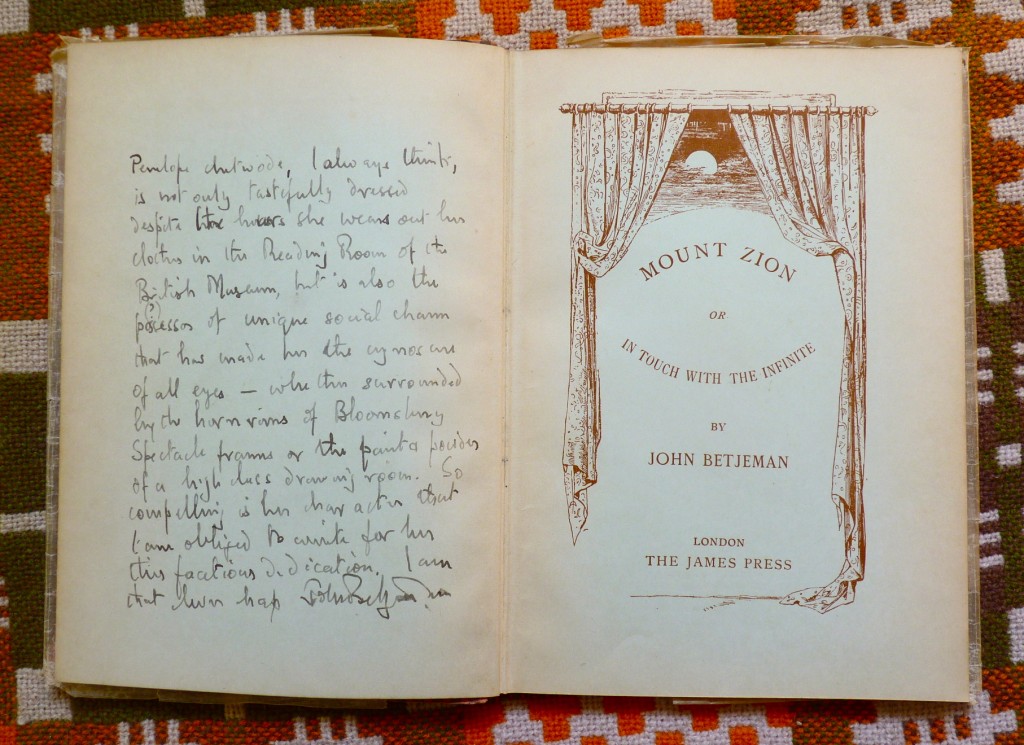

This copy of Betjeman’s first volume of poems Mount Zion (1931) was presented to his future wife Penelope Chetwode soon after they had met. In it he wrote :

‘Penelope Chetwode I always think is not only tastefully dressed despite the hours she wears out her clothes in the Reading Rooms of the British Museum, but is also the possessor of unique social charm that has made her the cynosure of all eyes… So compelling is her character that I am obliged to write for her this facetious dedication. I am that clever chap John Betjeman.’

The same facetious tone often colours his poetry, but Betjeman had the bardic power of enchantment. There, as here, his tone is a foil, lightly disguising a protestation of love, of beauty, tragedy or sympathy, the strong feelings and affections that made everything he wrote or said so eloquently real and true.

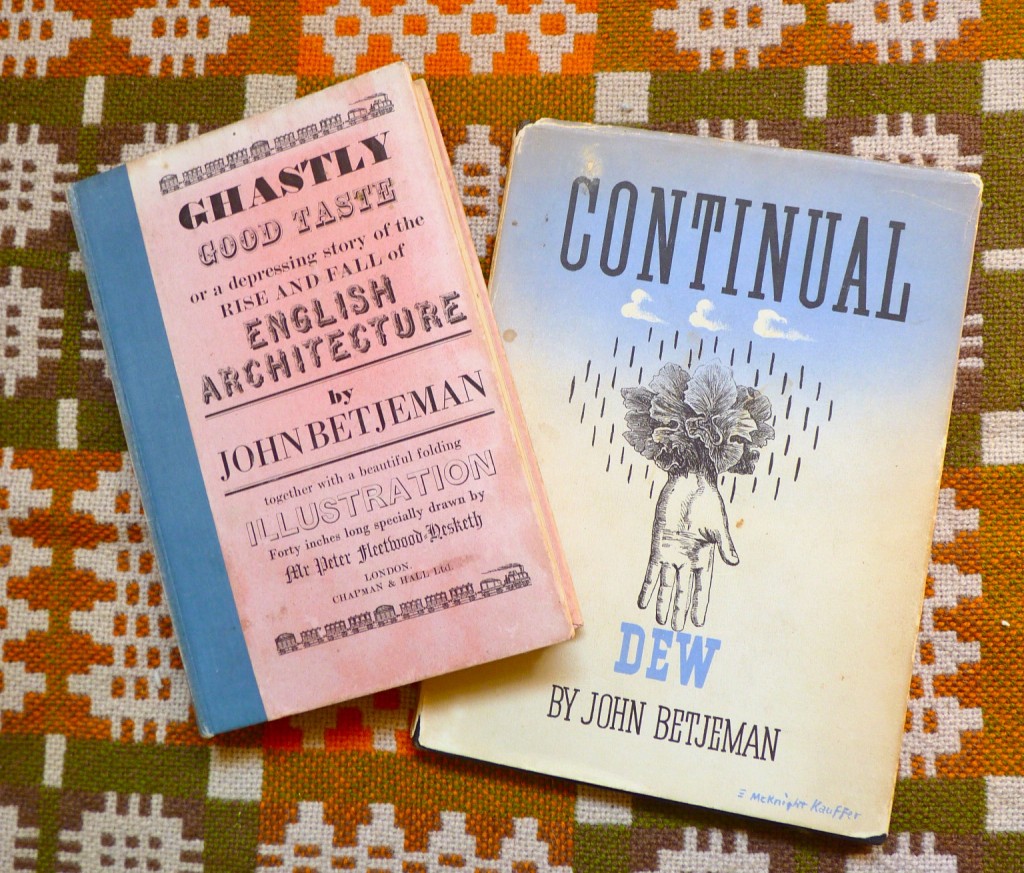

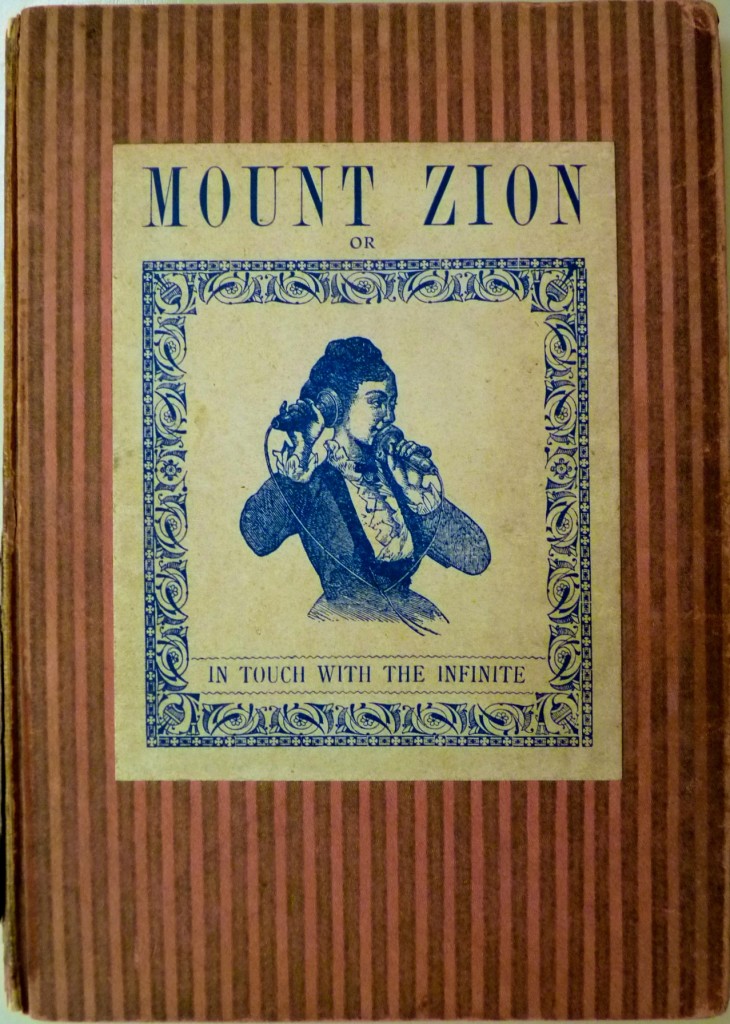

Mount Zion, or In Touch with the Infinite, published for JB in 1931 by Edward James, of who Salvador Dali is supposed to have said ,’ Of course, he is the most surrealist of us all.’

Further reading : Betjeman by A.N. Wilson

[All images copyright bibleofbritishtaste/ the estate of John Betjeman]

I am going through your older posts. What a good one!

Thank you for this post; but btw the cartoonist of Oxford University Chest is Osbert Lancaster, not O. Sitwell. I’m sure you’re familiar with Lancaster’s memoirs, All Done From Memory, but if not, I’d highly recommend them. There’s a wonderful cartoon of his, of singing ‘Sumer is icumen in’ with the Betjemans and some other unlikely characters, which I think is in there somewhere and also in A.N. Wilson’s Betjeman.

You are of course quite right and I have changed it. Thank You!