The French call the little, personal and inconsequential anecdotes that are most revealing of life, les petites histoires. Charleston Farmhouse is full of them, signposts and memoranda of the lives of the illustrious, clever Bloomsbury Group who painted in circles, loved in triangles and lived in squares in that unfashionable London quartier. Except that they didn’t – for as two world wars made metropolitan life more and more unattractive they gradually rusticated and settled down into this peaceful corner of Sussex. Virginia Woolf would die near here by suicide, drowning herself in the River Ouse during a depressive episode in 1941. Her sister Vanessa Bell lived on at Charleston for another twenty years in picture-filled rooms that were palimpsests of Bloomsbury’s shared decorative language; she was survived by her husband Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, and two of her three children.

Back in April Charleston’s director Nathaniel Hepworth invited me to make this photographic record of the farmhouse’s rooms and contents. Charleston has been shut up all this year, he told me, it receives no government grants and relies on the annual income generated by its visitors to keep going. Descendants and supporters of those who created this place are rallying round to fund this deficit: Vanessa Bell’s granddaughters have taken the cause to the USA with a piece in this week’s New Yorker magazine. ‘Charleston still smells the same to me. It smells like turpentine and old books,’ Virginia Nicholson reminds her sister. ‘You can feel the ghosts.’ The words and pictures that follow are to keep it alive in our collective memory and to rattle the collecting tin for this quietly beautiful and compelling place once again.

Below Firle Beacon, Charleston Farmhouse looks over the Sussex Weald

‘The house wants doing up and the wallpapers are awful.’ This was the verdict when the two sisters – the painter Vanessa Bell and the writer Virginia Woolf – first saw it. The farmhouse belonged to the Firle Estate and had been home to a succession of tenant farmers. Vanessa Bell was looking for a wartime refuge for her unconventional household of two little sons, Julian and Quentin, her lover Duncan Grant and his boyfriend, David ‘Bunny’ Garnett. Both men had determined against military service and needed to find ‘work of national importance’ to avoid conscription; hereabouts there was the opportunity to labour on the local farms instead.

They moved in in 1916, Vanessa, Julian, Quentin, Duncan and three indoor servants, a housemaid, cook and nurse, Bunny Garnett and a lurcher, Henry. Quentin would later say that parts of the house dated back to Elizabethan times, but its rooms had the character of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: low ceilings, pretty shutters and fireplaces, smallish rooms and narrow stone flagged passages.

This is the dining room, just within the front door. The round table came in 1934 and was painted and later repainted by Vanessa Bell when the pattern became worn.

In 1913 Grant and and Bell had joined with Roger Fry to found the Omega Workshops. Omega was a co-operative, controlled by the troika of Fry, Bell and Grant, bringing Post Impressionist colour and design to the applied arts. Their designs represented a fantastic bid for modernity back then. Fry was aiming for the spontaneous freshness of peasant or primitive work, so Omega’s productions were sold anonymously. Their premises at 33 Fitzroy Square attracted society people – Lady Cunard, Lady Ottoline Morrell – who bought Omega screens, chairs, pottery , textiles, necklaces, hats, fans, parasols, and opera bags, thrilled by their gaudy colours and elemental style.

There were paraffin lamps and they went to bed by candlelight. the chairs came from the Omega Workshop, designed by Fry in 1913. Quentin Bell made the pierced ceramic lampshade – which throws dotted patterns on the walls – later on, in his pottery here.

The stencilled wallpaper was Duncan Grant’s idea, in 1939, helped by Quentin Bell. The ‘polite’ ebonised cabinet was a relic from Vanessa’s childhood home.

Duncan Grant’s 1932 cat painting ‘Opussyquinusque’ was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in the same year.

From 1919-39 Charleston would mostly lie fallow as a holiday house. Six months after the war ended, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant were still living here with one servant, a cook named Jenny, Bell’s two sons and their new baby Angelica. In March Virginia Woolf bicycled over from her rented house at Ashham and found, ‘the baby asleep in its cot and Nessa and Duncan sitting over the fire… Duncan went to make my bed…By extreme method and unselfishness and routine on Nessa & Duncan’s parts chiefly the dinner is cooked, & innumerable refills of hot water bottles and baths supplied. One has the feeling of living on the brink of a move. In one of the little islands of comparative order Duncan set up his canvas, and Bunny wrote a novel in a set of copy books. Nessa scarcely leaves the baby’s room… The atmosphere seems full of catastrophes which upset no one…’

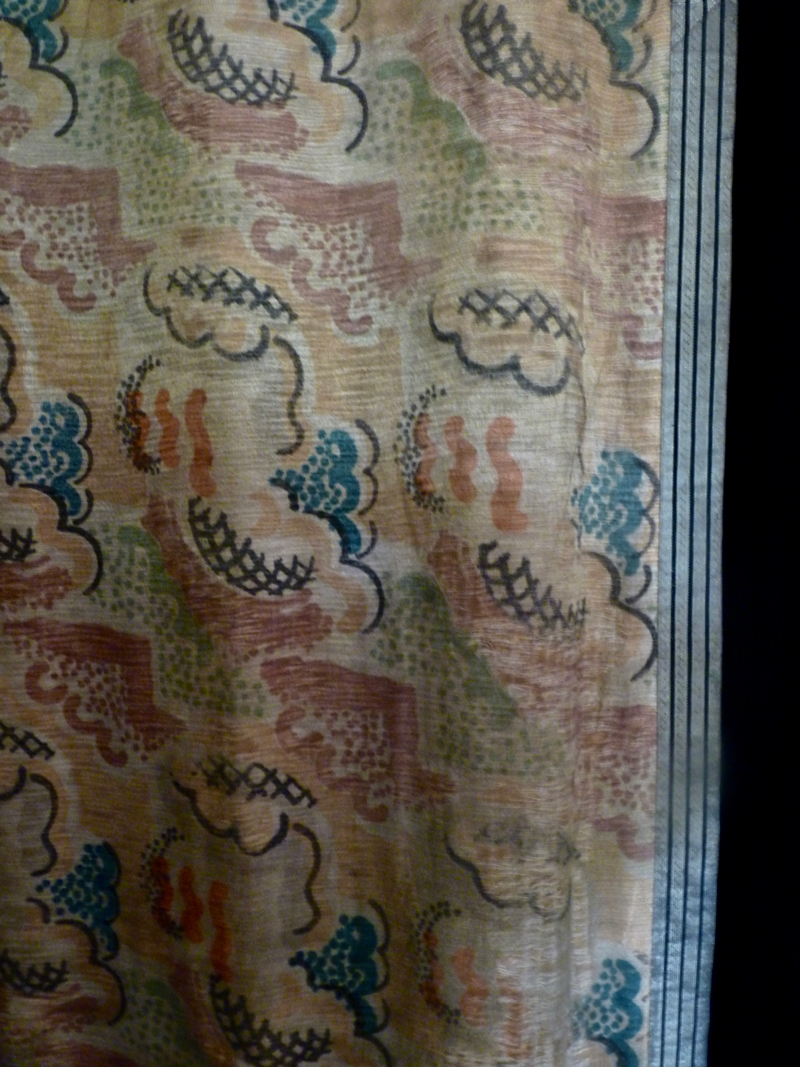

Marvellous curtains in contrasting strips of chintz, sewn by Vanessa Bell, shown by the hand of Kathy Crisp who is the Conservation Housekeeper here.

As they grew up, Quentin remembered laughter at the centre of their ‘odd family life … We laughed at and with Vanessa, she laughed at and with us, we all laughed at Duncan.’ Vanessa Bell is the genius of this place and her hand is everywhere.

The fireplace was enlarged and opened up in 1925.

Venetian side table

A few surviving plates from a dinner service designed by Duncan Grant for Clarice Cliffe. The covered soup bowls were made here by Quentin Bell. The tea caddy was decorated by Vanessa’s daughter with Duncan Grant, Angelica, in the 30s.

Curtain fabric – ‘Clouds’ – designed by Duncan Grant and printed by Allan Walton Ltd. hanging over a lobby giving onto the kitchen ( and for sale in the Charleston shop!)

In May 1919 Virginia Woolf was here for an overnight stay, alone with her sister – ‘as far as she can ever be alone,’ she told her diary. ‘There was Pincher the new gardener; Angelica; Julian and Quentin of course; the new nurse; & a fire which wouldn’t burn. They have bread by the yard…indeed, all the necessities; but not an ornament. …But they all looked as vigorous as possible… a good deal of domestic talk. Sleep in the ground floor room at night, where this time last year about I heard the nightingales, & the fishes splashing in the pond; white roses tapped at the window that night.’ But when the first world war ended everything was scarce, there was no coal, little wood, no butter, no meat and so Vanessa moved her household back to London, Charleston became their second, summer home.

In the autumn of 1924 Virginia called at the house, bringing her aristocratic friend Vita Sackville-West, ‘and how one’s world spins round – it looked all very grey and shabby and loosely cut in the light of her presence.’

But where did their very particular decorative taste come from ? Roger Fry had a significant role as their taste-maker. Brought up in a strict Quaker household, Fry’s austere preference was for uncarpeted rooms with bare polished wood floors decorated in pale greys and dull greens – an Arts and Crafts aesthetic but without what he dubbed its moral earnestness – because, ‘We have suffered too long from the stupidly serious.’ Bell and Grant embellished this pared back domestic style with the lavishly applied surface decoration that had characterised Omega’s furniture and ceramics. Vanessa Bell decorated this fire surround in 1925-6. Chair upholstered in Duncan Grant’s ‘West Wind‘ fabric ( which you can still buy in the shop).

During the 30s Grant and Bell had began to be spoken of as among the most prominent artists working in England, the founders of a new school of applied art. Fry hoped their enterprise would make a radical difference and even influence ‘the man on the bus.’

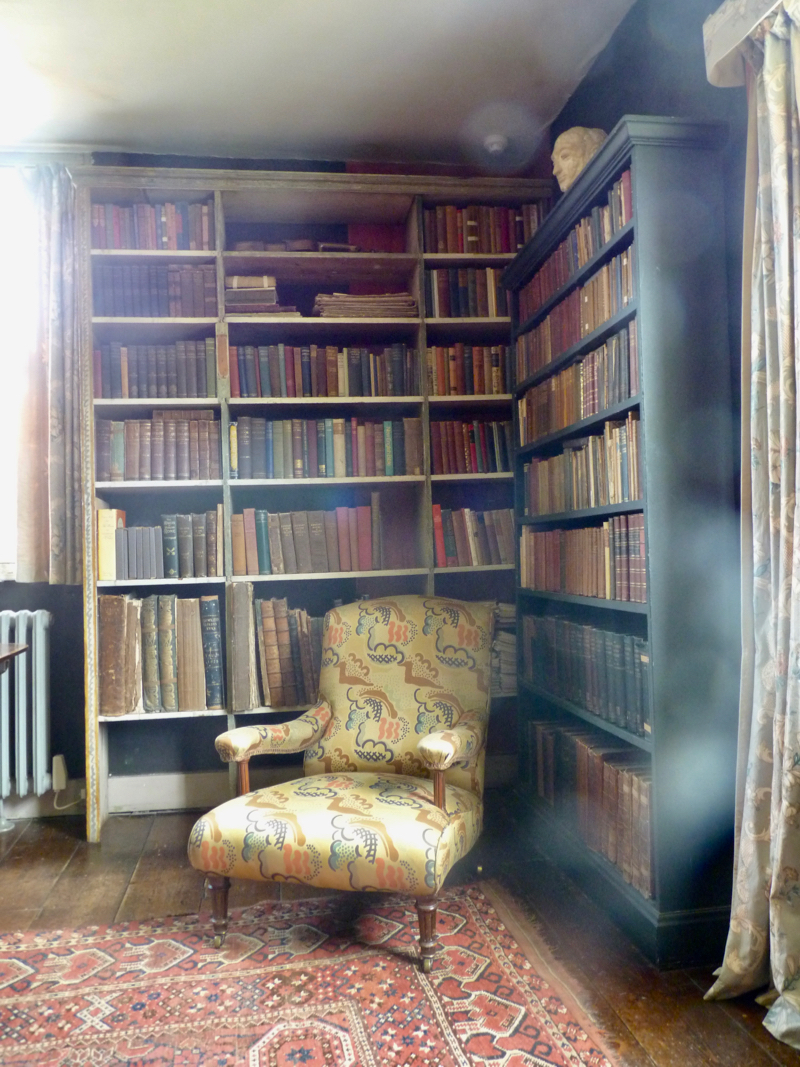

This is Clive Bell’s ground floor study but it began as the family’s living room, its big fireplace designed by the practical polymath Roger Fry to heat this ‘horribly cold’ house. Here during the years of WWI they eked out their meagre butter rations with marrow and ginger jam at teatime. A kind, placatory and distant father, Bell was only an occasional visitor during those years his children remembered, usually accompanied by his mistress Mary Hutchinson and bringing chocolates ! despite wartime shortages. (Clive was then living at Garsington, the guest of Lady Ottoline Morrell.) His son Quentin described him as having had several personae: the libertine, the hedonist, the sporting squire, the highbrow aesthete. This room became Clive’s study when he moved to Charleston in 1939, his arrival suddenly lending the unconventional household a new kind of ‘respectability.’ Quentin described his parents as ‘models of conjugal infidelity…. ours was an elastic home.’ Vanessa said that when she married Clive Bell, while he was not particularly attractive he was very amusing; later, during his bachelor life he became rather worldly and sometimes ridiculous in his pursuit of girlfriends.

‘Clive is writing a letter to the N. S. [New Statesman] against war. War’s so awful it can’t be right anyhow.’ Virginia Woolf’s diary, 20 September 1935. Clive’s fear of war ‘led him to try and find arguments for Fascism,’ causing a temporary rift with his son Quentin.

They did not much care if painted surfaces were not properly prepared or there was damp. If the table top’s decoration wore out they could paint some more on top. Door with panels of two dats.

On Xmas eve in 1918 the young Bell boys had fatally damaged the lower panel during a game of “The Sack of Rome.’ Their baby sister Angelica was born that night, the damaged door panel was eventually repainted in 1958 by Duncan Grant in this very different idiom.

door detail

The kitchen. Although Vanessa occasionally cooked, she preferred to employ a cook. The willow pattern platters came from Vanessa and Virginia’s childhood home, the Aga replaced an older solid-fuel range.

Grace Higgins joined this household in 1920 aged 16, and stayed for 50 years as maid, nurse, and eventually, resident cook and housekeeper. She married in 1934 and only retired in the 60s. Tiles made by Quentin Bell: ‘She was a good friend to all Charlestonians.’

Vanessa Bell’s painting of their long-serving cook, Grace Higgins, 1943.

lovely teapot by Quentin Bell

mug hooks and the servants attic staircase known as ‘High Holborn’

the cook’s books

‘Dined at Charleston. All seemed to agree that a country life is best. … Shall we not all provide ourselves with single rooms in London and live here?’ Virginia Woolf’s diary, 16 September 1938, on the eve of war. Vanessa decorated this kitchen cupboard in the 50s.

‘Human voices wake us and we drown – quotation on hearing the telephone yesterday asking us to Charleston. Bunny there; Angelica moody; conversation however well beaten up – Duncan’s 480 canvases; new studio: N’s bedroom on the garden; Q’s potting shed…Today they’ve chipped off the pink brick and removed the greenhouse shed….Now for the mantelpiece question. Then lunch.’ Virginia Woolf’s diary, 31 July 1939. Later her great niece Virginia Nicholson would describe the household as having a childlike quality, perhaps because Charleston was ‘hardly affected by the war,’ its kitchen being supplied from local farms and gardens.

As the oldest sibling Vanessa Bell embarked on her long stint of mothering and housekeeping fro the early death of her own mother, caring for her father, brothers and sister Virginia, then for Clive Bell, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant as well as her own three children.

Part of the very austere white dinner service designed by Roger Fry.

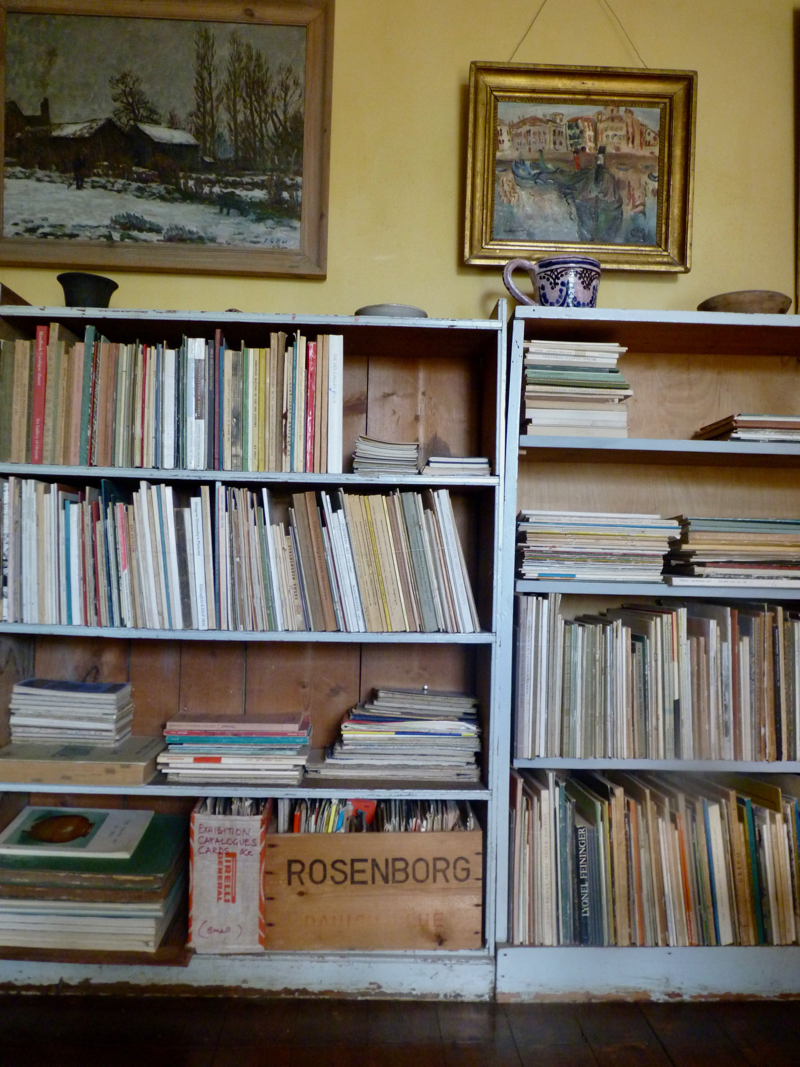

At the beginning of World War II Clive Bell decamped to live full-time at Charleston, bringing his library and furniture from Gordon Square in London with him. Vanessa, Duncan and their children were back here full time again too, and Vanessa now chose to refurbish the whole north end of the upstairs house for his accommodation, bedroom, new bathroom and library.

But not everything that went on here was idyllic. Quentin Bell remembers his mother being tediously and repeatedly teased by her husband at a supper when Picasso and Diaghilev were guests, until she lobbed a jam tart at his solar plexus, hard. Ruling over this tangled communal household could made her dictatorial and assertive, her sister Virginia called her ‘terribly monolithic and imperious – a terrifying woman in her way…’ Diary 8th April 1935.

The chair is upholstered in the ‘Grapes’ fabric designed by Duncan Grant in 1952 .

In 1917, when this had just become Vanessa Bell’s bedroom, Duncan Grant painted their lurcher Henry under the window and a cockerel on the pelmet above, ‘to guard her at night and wake her up in the morning.’ But Henry terrorized the servants and was soon got rid of. Grant based his own moral philosophy on G E Moore’s Principia Ethica published in 1903: ‘The best ideal we can construct will be that state of things which contains the greatest number of things having positive values and which contains nothing evil or indifferent.’ Judgement belonged with the individual and he accepted people just as they were; this made him very attractive to friends and lovers but as Quentin Bell also remembered, ‘he was rather a cold-hearted bugger.’

With this increase of the household came the improvement of mains water and new bathrooms. Quentin Bell said : ‘there was the bathless period,1916-1919, the bath period 1919-1939, and the multi-bath period from 1939.’ First of all there had been cold water only and a hip bath. This room was formerly a picture store; Clive Bell claimed this bath for himself and the rest of the household used the one in Virginia’s new bedroom, where the cook Grace was also allowed to bathe on Tuesday afternoons.

The 1970 painted bath panel is by Grant’s friend Richard Shone, a former editor of the Burlington Magazine.

Lotions and potions. Angelica Garnett described Clive Bell emerging from this room ‘pink as a peach, perfumed and manicured but in old darned clothes of once superlative quality; he would enter the room and tap the barometer, the real function of which was to recall his well-ordered Victorian childhood.’

The bathroom and Clive Bell’s bedroom

Clive Bell’s bedroom , initially his wife Vanessa’s studio

Bell’s French provincial bed – painted by Vanessa in the 50s – ended up in the possession of his last mistress, Barbara Bagenal, who eventually returned it to Charleston

Mild erotica, drawing by Andre Dunoyer de Segonzac over the bed

Bedside table probably decorated by Vanessa Bell in 1920

Duncan Grant decorated this corner cupboard in 1925

Vanessa Bell designed the fabric on this armchair for Omega in 1913 ( still for sale in the Charleston shop).

Bell’s French novels and the paintings given to him by French painters

Books versus pictures: Virginia Woolf’s diaries record bouts of insecurity as she compared her own creative life with her sister’s: the life of a writer in semi-retreat as opposed to the rough and tumble of a large household, painting, children. In the spring of 1930 she was in London, exulting over her own writing yet brooding on her sister’s life here: ‘ they will have the windows open; perhaps even sit by the pond. She will think: This is what I have made by years of unknown work – my sons, my daughter, she will be perfectly content (as I suppose) Quentin fetching bottles; Clive immensely good tempered.’ Her 1934 essay on Walter Sickert concludes that :’Words are an impure medium… Better far to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint’.

Maynard Keynes, – Duncan Grant’s ex lover who worked at the Treasury and their most frequent visitor in the 20s, – was eventually given his own bedroom next door to Clive Bell’s; post-WWI having worked on the Versailles Treaty, he resigned and lived here more or less permanently until his marriage in 1925. Then when this became Quentin Bell’s bedroom his mother purged its decoration and painted it white and pale grey.

The firescreen was decorated by Duncan Grant in the 1930s, above is Vanessa Bell’s view of the house

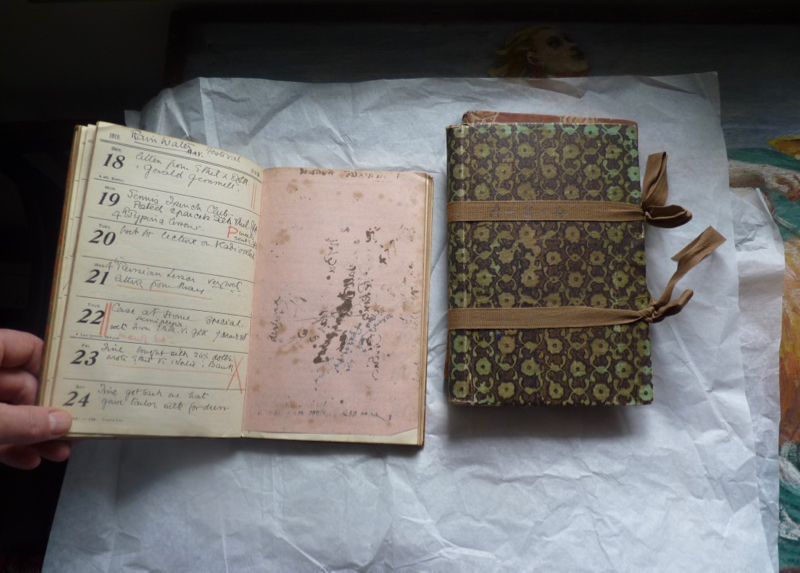

Decorated box files hold documents for a life of Virginia Woolf collected by Quentin Bell.

Virginia Woolf kept herself divorced from domesticity, her husband Leonard managing all their affairs. She was alternately envious and exasperated by the fluctuating household at Charleston and its high levels of domestic labour, she told her sister, ‘How much I admire this handling of life, as if it were a thing one could throw about; this handling of circumstance!’

But she was a devotee of the Bloomsbury-Fry aesthetic creed. She was frequently teased for her love of the green distemper paint that she used extensively at Monks House and she shopped for Omega’s yellow, pink and terracotta furniture too. In ’39 she wrote to her sister, ‘ Have you got one of those tile tables? If so, what price? Or could you make me one?’

Lily pond table by Duncan Grant, c.1913, the rush-seated ebonised settle was a gift from Mary Hutchinson to her lover Clive Bell.

Superb linen chest painted with a bather by Duncan Grant c.1917.

Inside the lid is a mythological scene, ‘Leda and the Duck.’

Morpheus, god of sleep, on the bedhead painted by Grant for Vanessa Bell.

Mattress ticking,

Corner of Duncan Grant’s bedroom, he bought the prie dieu in Brighton in 1918

Quentin Bell remembered that Grant was ‘certainly not a father-figure to me – more of an elder brother. As Angelica’s father he was non-committal and really rather limited. Although he cared for her I don’t think he cared for the whole situation very much.’ Charming and unselfconscious, Duncan Grant seemed selfish in his pursuit of male lovers. Vanessa Bell suffered anguished jealousy but resigned herself to this, justifying her situation, ‘ he likes being with me enough for me to be quite happy.’

In February 1918 Vanessa Bell had painted marbled circles and flowers on the doors either side of the fireplace in what later became Duncan Grant’s bedroom

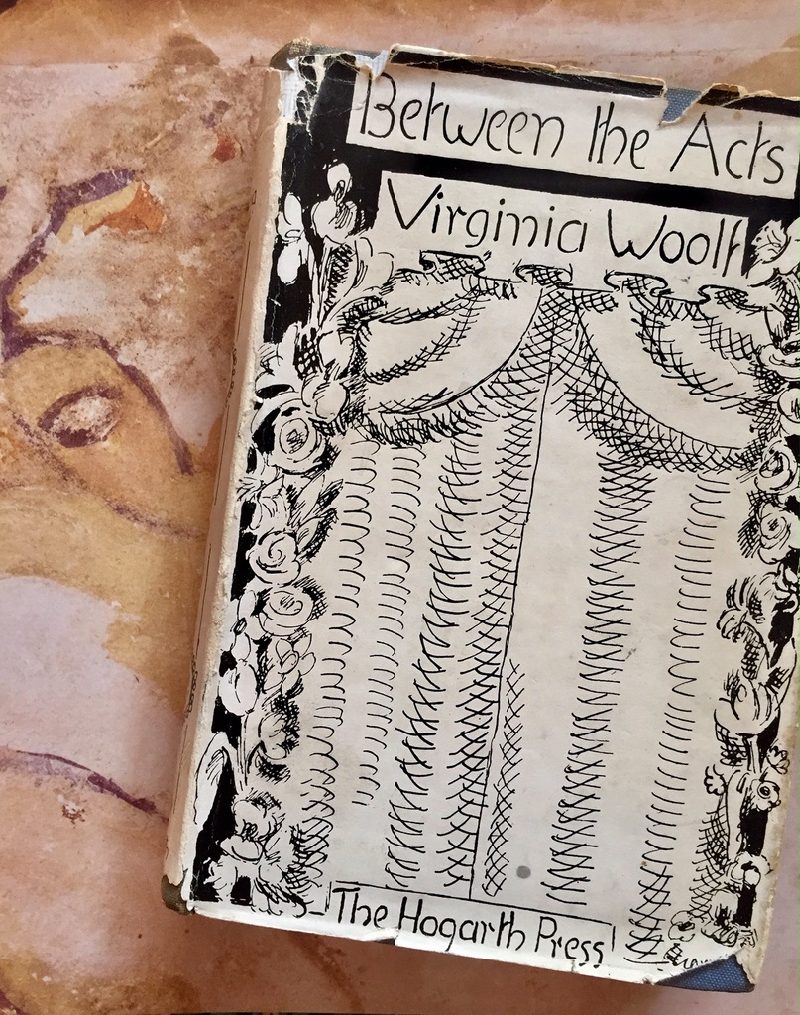

Vanessa Bell kept a sisterly accord with Virginia but did not always read the books that she designed for her. Bell’s book jackets used the same motifs of flowers, curtains, circles and hoops as she painted onto her furniture, symbols of plenitude and nourishment.

Between the Acts was written at Monk’s House, Rodmell, completed in 1941, the year of Woolf’s death and published posthumously later that year. These Hogarth Press books were meant for the common reader and not intended to be lasting objects of beauty – this battered copy, my father’s, bought when he was captain of an army field hospital during WWII, retailed at seven shillings and sixpence. Vanessa Bell was designing for her contemporaries, making lively abstract patterns that translated fluently into line block printing on cheap paper, much as she would paint quickly onto a cupboard door or table top at Charleston. Virginia told her sister, ‘Your style is unique: because so truthful: and therefore it upsets one completely.’

Painted window surround

Chintz upholstery designed by Duncan Grant in 1951

Duncan Grant’s dressing room, his painted silhouette portraits of his ancestors, fabulous V. Bell lampshade

Painted table top by Duncan Grant

Amongst Duncan Grant’s library, intrepid travel journals kept by his aunt

The garden room or drawing room:

One visitor observed that here, ‘arguing was regarded as a delightful sport;’ above the sofa is Vanessa Bell’s copy of Poissy-le-Pont by Vlaminck, a painting that they were obliged to sell in a period of penury.

Vanessa Bell designed the paisley pattern stencilled onto the walls in the 40s at the end of the war; Duncan Grant designed the curtain textile in 1951 for Alan Walton Ltd.

‘It is a very shabby house which we have been in for twenty years now and gradually got more or less furnished – only as soon as one room gets in order another seems to fall to pieces.I have painted lots of walls myself and made all the curtains, covers, and everyone has had a hand in it. So it’s pleasant for artists if for no one else, as it has at least very little mechanical quality.'[Vanessa Bell]

But herein lies the fascinating, apparently effortless ‘simple life’ aesthetic that makes artists houses so attractive to us. The Charleston Bloomsburys sustained the lifestyle of stylish peasants with three servants, a plain white dinner service designed by Roger Fry, idiosyncratic bespoke furniture and pottery thrown in the garden studio. Duncan Grant’s mother Ethel translated their designs into needlework rugs and cushions. All life here was homogeneous and happened on their own terms. Everything in the house passed this process of moral and aesthetic filtering: so that, as one critic has tellingly put it, ‘a visitor entering was made immediately aware that nothing had been chosen to display social standing or material wealth,’ a carefully achieved distinction.

T.S.Eliot prized Bloomsbury’s uniquely high standards of conversation that had raised his own game too, the deployment of silences, pauses and theatricality, ‘opportunities for the other person to show his wit.’ At her best Virginia Woolf offered ‘gossip, sparkling gaiety and delicate malice,’ the same gifts she used as a critic, Vanessa remembered that, from her childhood ‘speech became the deadliest weapon as used by her.’ There was also mockery, wounding contempt and a degree of insularity. Virginia and Leonard referred to themselves as ‘the Woolves.’ ‘Tenuousness and purity were in her baptismal name and a hint of the fang in the other,’ wrote her friend and sometime lover, Vita Sackville-West.

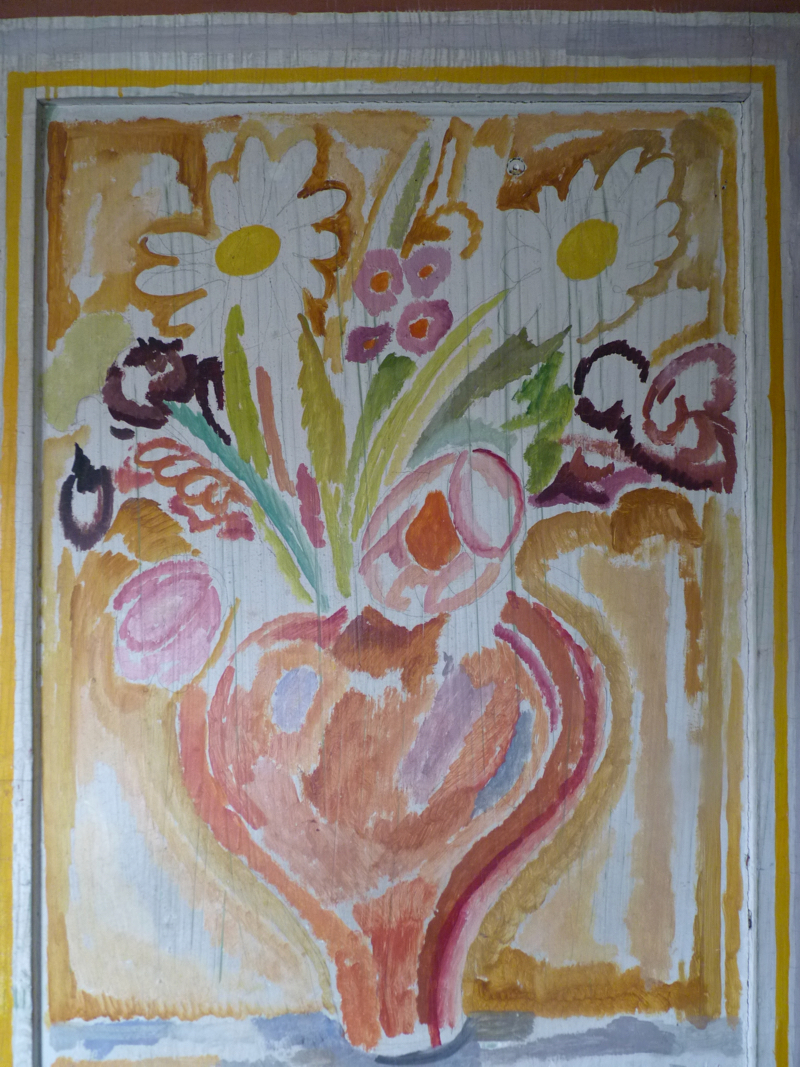

The painted overmantle replaces a mirror cracked by an Aladdin lamp.

NB ceramic lion on the chimneypiece

A room in which Vanessa and Duncan used to fall asleep and company gathered for a drink and smoke before supper. The long French windows give onto the garden. The wireless was kept here too.

In 1937 Vanessa Bell’s elder Julian was killed in the Spanish Civil War at the age of 29, while driving an ambulance. During the years afterwards ‘Charleston seemed the saddest place in the world.’ His brother Quentin always associated this room with the tragedy of that time.

In this little fireside table drawer, packages of Julian Bell Cash’s school name tapes are housed in memoriam.

But why Virginia Woolf chose the period immediately after her nephew Julian’s death to tell her niece Angelica that Duncan Grant was her real father , and not as she had always supposed, Clive Bell, is ‘hard to fathom,’ her half-brother Quentin has suggested. This was where she did so.

downstairs lavatory

Vanessa’s Bell’s ground floor bedroom was originally the household larder. She painted the tall cupboard in 1917. It’s full of portraits of her children, her mother’s photograph and a sultry self-portrait of Duncan Grant taken when he was about 25.. Her son Quentin has described her very acutely as – ‘ the firm pillar of our existence. She was sensible, practical, imperturbable… she didn’t talk much but she controlled everything’ – and an extraordinarily good painter with a kind of nobility and austerity to her work. ‘Yet she always thought Duncan was a better painter than she. Perhaps in old age that was true, for she had a tendency to go off into a kind of sentimental world of flowers and children. She loved her grandchildren too much and it wasn’t good for her painting.’

This Omega Workshop screen in Vanessa Bell’s bedroom was painted by Duncan Grant in 1913 and exhibited in their Fitzrovia opening exhibition; it divides bathroom and bedroom. The bath was installed in 1939 when the household expanded in wartime and painted by Duncan Grant in 1945. But with the end of the war Bloomsbury’s short lived artistic ascendancy ended too. Evelyn Waugh was quick to reference this in his debut novel, Brideshead Revisited, (1945) with an Oxford undergraduate, Charles Ryder, for its protagonist:

On my first afternoon I proudly hung a reproduction of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers over the fire and set up a screen, painted by Roger Fry with a Provencal landscape, which I had bought inexpensively when the Omega workshops were sold up….My books were meagre and commonplace – Roger Fry’s Vision and Design, …

When the drunken aristocrat Sebastian Flyte puts his head through Charles Ryder’s open study window and vomits after drinking wines that were ‘too various,’ Charles is invited – by way of an apology – to a luncheon party in Sebastian’s student rooms at Christ Church, high up in Meadow Buildings.

When at length I returned to my rooms and found them exactly as I had left them that morning, I detected a jejeune air that had not irked me before. What was wrong? Nothing except the golden daffodils seemed to be real. Was it the screen? I turned it to the wall. That was better.

It was the end of the screen. Lunt had never liked it, and after a few days he took it away, to an obscure refuge he had under the stairs, full of mops and buckets.

Washstand, 1917, by Vanessa Bell.

Staying in this room in May 1919, Virginia Woolf had written: ‘Sleep in the ground floor room at night, where this time last year about I heard the nightingales, & the fishes splashing in the pond; white roses tapped at the window …’

When Vanessa Bell died here in 1961, Duncan Grant wept, repenting of his cruel treatment of her: ‘I could have been kinder to her,’ he said. Clive Bell outlived his wife by 3 years.

In 1925 a longer lease on the house was negotiated and the L-shaped studio was constructed, planned by Roger Fry to whom Bloomsbury deferred in these matters. Fry said ‘the great object is to have as much room and spend as little money as possible.’ Quentin Bell called these years from 1925-1937 the Golden Years.

‘it ought to please the feminists,’ said Duncan Grant of the dinner plate designs by Bell and Grant, part of the Famous Women Dinner Service commissioned by Kenneth Clark in ’33 when he was director of the National Gallery and in order to revive Grant’s interest in the decorative arts. Grant and Bell went to stay with Josiah Wedgwood and experimented on Wedgwood blanks; the Dutch walnut cabinet belonged to their kinsman the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, inherited by Vanessa Bell from her father Sir Leslie Stephens.

The fireplace surround was painted on hardboard by Duncan Grant in c.1932, he painted the decoration above the mantleshelf between 1925-30

The Pither stove that kept them all warm in winter

At first, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant shared this space, working here together ‘like two sturdy animals side by side in a manger…’

The far corner of the room doubled as a useful dressing room for models or a backstage for family theatricals.

Duncan Grant’s easel, his male nude of 1934. Their own pictures were out of fashion and stopped selling so they sold a Poussin and the Vlaminck.

figures of Adam and Eve painted inside the cupboard doors by Duncan Grant

Duncan Grant’s painting kit still covers the table top.

In winter the warmest room in the house, the studio doubled as a sitting room.

Bust of Virginia Woolf on an eighteenth century chest of drawers

Duncan Grant died in 1978 and the Charleston Trust was established in that year; by the 80s his painting was beginning to be venerated again.

Duncan Grant’s cast of the ear of Michelangelo’s David obtained from Lewes art school

On her childhood holidays here, Virginia Nicholson remembered the lovely smell of new cake, books and turpentine, dahlias, and sweet lavender drying in the spare rooms.

‘The house is now closed indefinitely with a half a million pound loss that we need to fund to be able to survive the autumn and winter. This time next year, we will need places like Charleston to visit …we will need museums and galleries which hold our national stories and protect our cultural treasures. Charleston is an internationally important part of England’s cultural heritage. Please help us to save this special place. ‘ Nathaniel Hepburn, Director of the Charleston Trust.

broken crockery mosaic work contrived by Duncan Grant, here being cleaned by a team of volunteer garden workers.

Garden volunteer’s cool home-tailored jacket.

Part of a torso which once stood by the pond, broken and knocked in by Quentin Bell’s son Julian, retrieved and converted into this planter by Quentin. Casts are for sale in the Charleston shop

Greenhouse

Charleston gardener Harry, @harry.saxatalis and Charleston lettuce

sweet peas. Before Bloomsbury the garden consisted of this kitchen garden housing a scrappy wild orchard and the garden proper and pond in front of the house. Roger Fry laid it out afresh with new beds and paths at the end of WWI, there were roses, the abundant globe artichokes, fruit trees, hollyhocks, poppies, marigolds and dahlias and butterflies – a colour filled painter’s-cottage-garden.

dahlias

cast of Antinous topping the brick and flint garden wall

Globe artichokes

head of Hermes, copies for sale in the shop

Concrete urn on the gatepost

more herbage and July florals

flaming July

‘Ours was an elastic home , it never broke,’ Quentin Bell

Grateful thanks to Charleston’s resourceful director Nathaniel Hepburn and Kathy Crisp, my guide for the morning. (art school trained, she also has a cottage industry making very desirable ‘Bloomsbury’ lampshades at chapelhousestudio.bigcartel.com

NB Read Vanessa Bell’s granddaughters Virginia Nicholson and Cressida Bell in the print edition of the New Yorker August 17, 2020, issue, “Rooms with a View.”

AND PLEASE DONATE GENEROUSLY to the Charleston Emergency Appeal: https://www.charleston.org.uk/charleston-emergency-appeal/

If I turn my head to my right, there is a photo portrait of Virginia Woolf, the one by Gisèle Freund, Nigel Nicholson’s favorite, telling me ow great your eye is. She also tells me she is still there among those she mocked and loved.

The Dunoyer de Segonzac drawing looks very much those he made of the writer Colette for “La treille Muscate” in the late 20’s.

Thank you again!

Beautiful Photographs ! Thank you . Interesting article too .

However

I do not understand WHY it all has to be closed up ? ? They don’t give a reason. They have huge Exhibition space & barns too . It seems odd to not open something . Surely some money better than none .

?

The rooms and passages in the farmhouse are tiny, not possible to have one way systems or spaced out visits so some much needed repairs to the house are being carried out instead and in readiness for next year.

I so look forward to these posts, and have been checking back from time to time for a new one. This surely did NOT disappoint!

Marvelous place and I plan to buy something from the shop to help support. But a few questions:

Who cooked, washed up, did laundry (no hot water at first, remember….), dusted, cleaned for all these people? Who gardened, washed the baby’s nappies? What were they paid? What were their working hours? Did they have fires in their bedrooms? Why do we not see the servants’ bedrooms and barely see the kitchen and sculleries among all these photographs? How telling that Grace Higgins, the housekeeper and “friend to all Charlestonians” (apparently she wasn’t one although she lived and worked there for 50+ years) was “allowed” to have one bath a week. I’m surprised that the servants are still invisible, even in 2020.

I lived in Charleston from 1995 to 2002. We used to smoke in the house, in the kitchen, New Studio, Vanessa’s Studio and in the gardener’s flat. I did all my cooking on the Aga and used many of those cookery books. On the shelf above the Aga at the left hand end is an ashtray made by the Omega workshop that I dug up in the garden halfway between the Garden Room doors and the Duncan’s Studio when I was changing the gravel. It was always used by Olivier when she was in the kitchen. The original packet of Gauloises cigarettes was left by Germaine Greer when she was a speaker at the Festival over 20 years ago. They started life at the other end of the shelf. The house and garden look far cleaner and neater than I remember and certainly in Vanessa and Duncan’s time would have been far more dirtier and chaotic. It looks much more like a museum than a place where people actually lived.

Nice pix. Duncan Grant was not Vanessa Bell’s husband, as stated, but a gay friend who fathered Angelica Bell.

I think you’ve misconstrued the text – to clarify, ‘she was survived by her husband [Clive Bell], Duncan Grant, and two of her three children.’