‘Have you lifted your leg on the place?’ The question erupts from my portly and moustachioed neighbour at a dinner given for members of the Historic Houses Association. I have barely been introduced to Sir James Cayzer and am somewhat surprised by his opening gambit, but I do not tell him I am not a dog because I am in my thirties, he is in his sixties and this is the 1990s. He had avoided the risk of anyone but himself lifting a leg on his place by never getting married, but this was an era when husbands with handsome old houses were in grave danger of finding them ‘done up’ up in flounces and frills, and their wallets much depleted by the exercise.

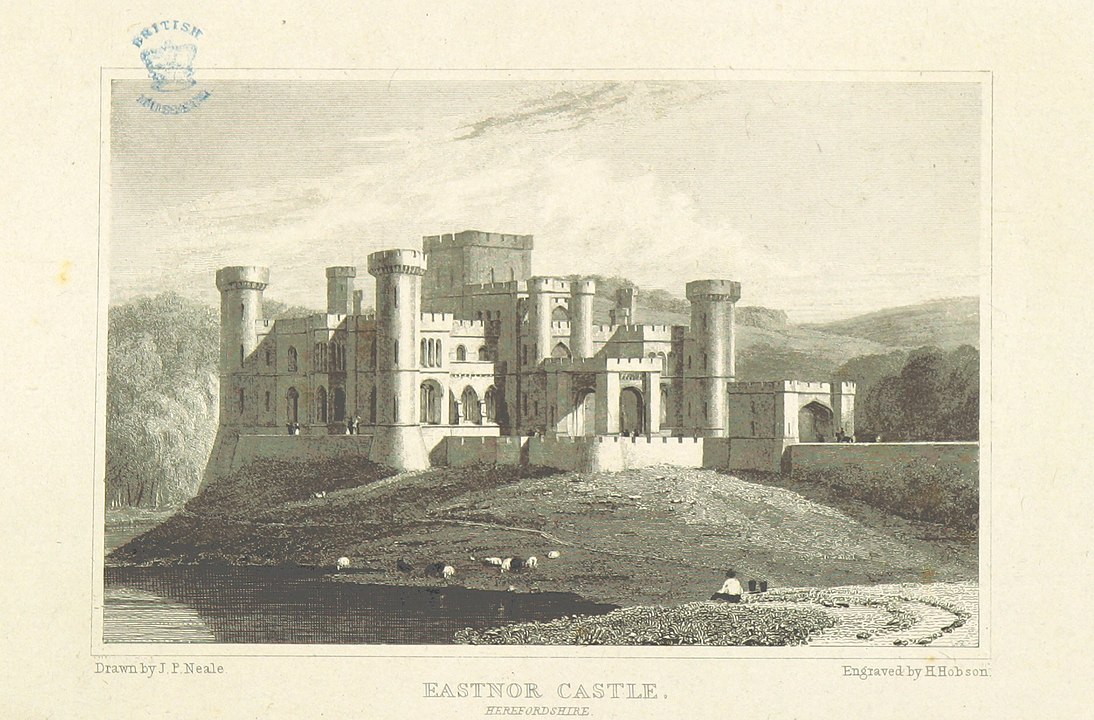

Perhaps it should not have come as a surprise to find a strict hierarchy amongst members of the HHA – the lobbying group of the over housed and underfunded – and when I married in 1982, Eastnor Castle was somewhere near the bottom. Just as my mother would shudder whenever we passed St Pancras in a taxi, so those who aspired to taste knew for certain that Eastnor was a Victorian horror – except that it wasn’t.

Eastnor was a Regency gothic revival castle in the Norman style (believed to be patriotic) built in stern repudiation of the revolutionary forces sweeping the continent in the early 19th century. True, like many big houses (97 rooms) it needed to find its late 20th Century purpose, but that was no reason to condemn it, and my seat next to Sir James at the dinner was a measure of the revival in Eastnor’s fortunes that had taken place.

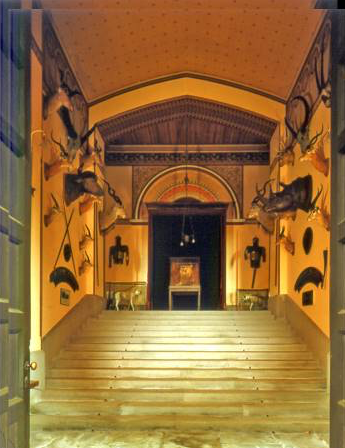

James Valentine, Great Hall, C19th, copyright National Galleries of Scotland

Sir James’ was near the top in the HHA hierarchy, not because his house was old or celebrated or attracted large numbers of visitors but because his wealth ensured that his pre-war lifestyle remained unchanged when inheritance tax had decimated everyone else’s, or almost everyone else’s. The dukes had no need of the HHA, and Sir James, too, could afford not to be bothered, but the fact that he did bother was a boost to the morale of those who were recreating the best of the past not for their own enjoyment, but for that of the public whose support was essential to maintain it. Sir James’ was right to suppose a leg had been lifted at Eastnor but the leg belonged to Bernard Nevill; I only followed on.

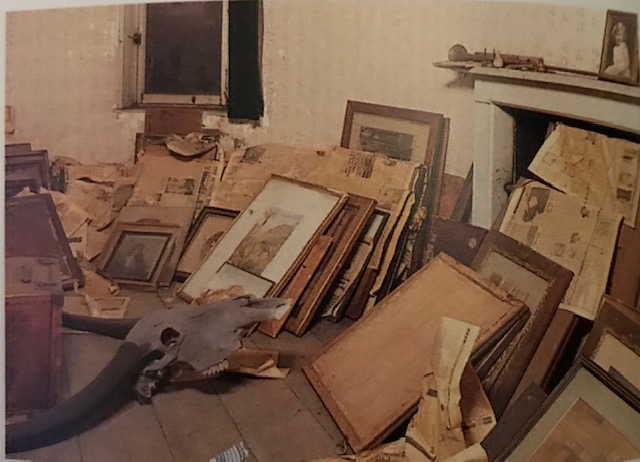

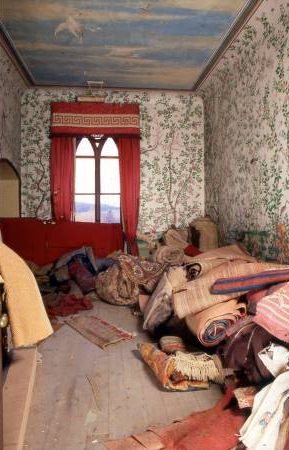

We moved in to Eastnor with our two year old daughter Imo in 1989, after the untimely death of my mother-in-law, Shib, to whom it belonged. The contents of the castle had been stored away for the war and most were never unpacked. What was the point when the old way of life had ceased to exist? Of the twelve guest bedrooms, only four were brought back into use.

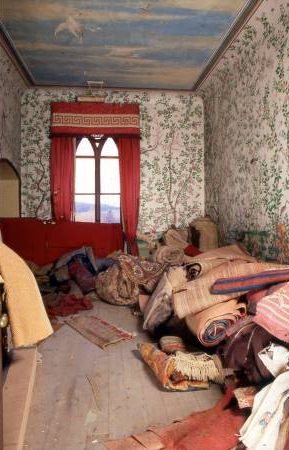

Before and after – the Red Bedroom before its redecoration in 1991

Post war, my father-in-law reinvented himself as a farmer and it was not unusual to find Shib scrambling over the four acres of roof, replacing slipped slates. Demolition was considered but dismissed as unaffordable and truth to say ‘the Castle’, as it was always referred to by the family, was like a grand old relation; demanding but always worthy of respect and no less loved for being low priority when estate cottages needed to be modernised.

The attics

Times had changed, but restoration was still a big gamble; how far would people travel to visit, the nearest big cities, Birmingham and Bristol, were an hour away? Most people thought we were insane to try, others were convinced we’d fail: their attitude served only as incentive. The low opinion of those with received taste was a blessing; there were no wing chair experts waiting to pounce on every move. We had a limited budget and needed advice, but who to ask? Imogen Taylor, doyenne of Colefax and Fowler, may not have seemed the obvious choice but she was a safe pair of hands and she came to look. She sighed when she saw my father in law’s old dressing room, the single bed in the corner, the air of worn austerity; she had seen so many others just the same.

Lord Somers’ Dressing Room, before

Nothing about the monstrous place appealed to her but she felt sorry for me and offered to help. She meant to be kind, but I did not want her pity. Brought up on Grimm and ghost stories in the Yorkshire moors, the castle held no terrors for me. I felt sure it would appeal to the child in others too, but not if traduced by chintz. And then a friend, Lucy Astor, suggested Bernard.

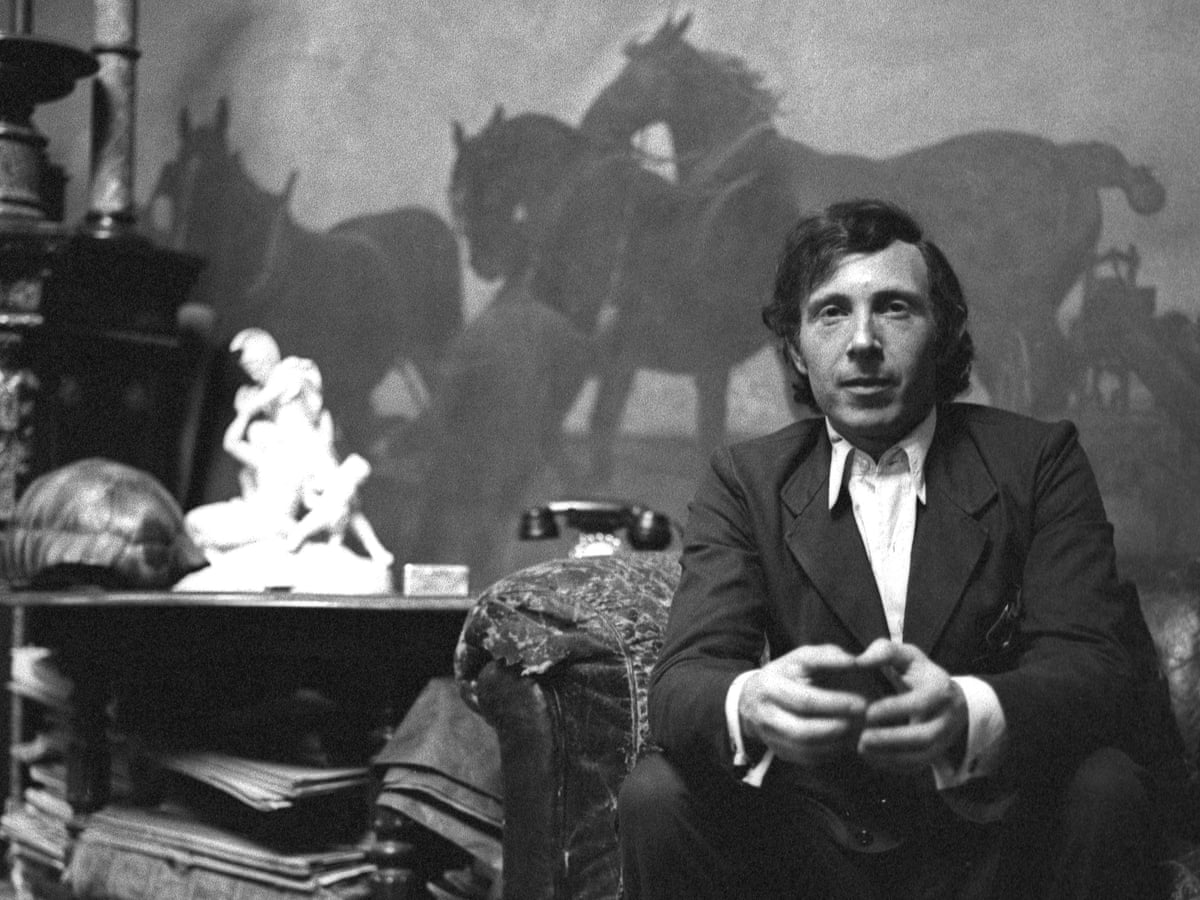

Professor Bernard Nevill photographed in Glebe Place (below) , his Chelsea ‘country’ house

We were invited to tea at Glebe Place, the country house Bernard had created in Chelsea, and were instantly seduced by the atmosphere; relaxed, generous, welcoming and comfortable; in the grand style but not smart, the ravishing rooms glowed like the log fire at which he warmed the coats of his departing guests. Bernard was Roman Catholic and the theatre of the divine in dimly lit and ornately decorated chapels was a rich seam mined to secular effect. Everything looked old, but was often not as old as it appeared; huge sofas, for example, were made to his own scale by Howard and Sons, after an Edwardian design.

Bernard’s official job was Professor of Textiles at the Royal College of Art, appointed by his friend Jocelyn Stevens, the Rector. He had started his career in the late 50s lecturing on the history of fashion to students who would go on to become the celebrated designers of the 60s. He had been something of a dandy back then and it was a source of regret, he told us in his wheezy voice, that he could no longer fit into his sharply cut suits. Luckily his interests had expanded commensurately and his knowledge of country house interiors of the Edwardian and Victorian periods, gained from poring over photographs in his archive collection of Country Life magazine and attending country house sales, was exhaustive.

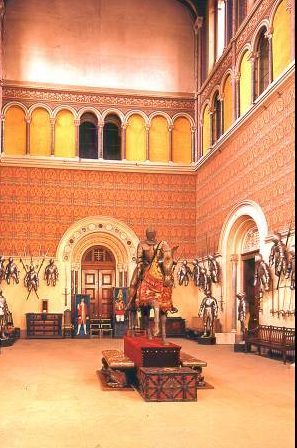

Entrance Hall with armour and taxidermy, prior to redecoration

Bernard’s background was wreathed in mystery; his lonely childhood was spent in Devon with two great aunts after his young parents moved to South Africa. This was of no great significance, he assured us, as he believed himself to be the re-incarnation of William Beckford, and had even secured a fragment of the stables of the ill-fated Fonthill Abbey as his Wiltshire base. As Beckford, born in 1760, dying in 1840, spanned the Romantic period between the 18th and 19th centuries, so Bernard moved unusually easily between the Edwardian and Victorian eras.

Entrance Hall rehung with portraits and suits of armour by Bernard Nevill

Everything about Eastnor appealed to him, not least its masculinity and scale – nothing was ever too big for Bernard. The front door, perhaps twenty feet tall, was just like the one at Fonthill Abbey, he told us, where Beckford employed a dwarf to greet guests and make it appear even taller; our small daughter could be deployed to the same effect, he suggested with a wry laugh.

The deal was that Bernard would be paid a flat fee for a number of consultations, most on site but others to include visits to workshops and auctions. In the State Rooms at Eastnor, lack of money and opportunity for use ensured nothing had stirred for decades; even the cold had turned gelid with gloom. Bernard arrived and blew through them like a hurricane, throwing everything in to the air and stirring everyone up. The Works Department, long used to suiting itself, tutted and grumbled as they reluctantly moved furniture out of storage to be offered up not in one location but in three or four, until Bernard, covering one eye with his hand to picture the effect, matched a piece to its setting.

The Chinese Bedroom with its hand-painted wallpapers , then a carpet store.

To them it looked no different here or there and the fact that Bernard did not appear to know what he wanted, hadn’t a clue in other words, was grist to their mill and made him an object of resentment and ridicule. Not only the Works Department, the ancien regime in all its aspects was appalled as the Castle was dismantled before their eyes. Scorn was one of Bernard’s strengths; he didn’t give a hoot. You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, and Eastnor was one enormous omelette. Heedless, he padded about in his black leather trainers, deaf to the sound of crunching eggshells.

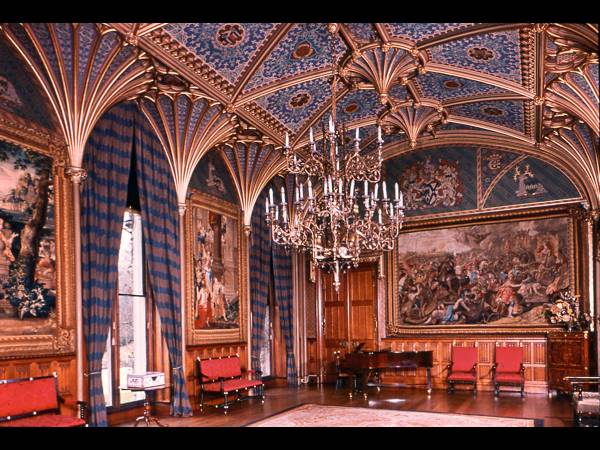

Great Hall before…

and after…. (sofas have since been reupholstered)

Those unacquainted with the creative process do not understand that what looks from the outside like destruction and chaos is vital to the outcome, but gradually the rooms began to take shape. The Great Hall is the first room the visitor encounters. Lofty, empty but for armour, cold and draughty, it became Bernard’s triumph. He transformed it into an Edwardian Living Hall, with giant sofas like his own covered in a pair of old velvet curtains and scattered with fur travelling rugs and big cushions, filled with 100% down.

The flagged floor was strewn with Turkey carpets from Magda, his friend in Bond St; her rugs were good value, but you had to check the colours hadn’t been painted in by her workshop.

A circular table of suitable scale was made out of plywood by the Works Department and covered with an Ottoman rug in the manner of a Dutch painting.

Another corner was filled by a Dutch cabinet topped with Delft vases, above which a mirror with a deep ebony frame was tipped to reflect the intimate scene. This was achieved by ecclesiastical candlesticks of all sizes, wired up by the late Mr Sitch of Soho and then shaded with either vellum coloured card or soft silk pleats to create pools of warm light. On either side of the two fireplaces giant brass candlesticks gilded the firelight.

I saw tough men, invited to Eastnor by Land Rover to drive the latest mud busting model, enter this room braced against the wealth, elitism and class they expected to find there and then, believing themselves to be alone, I watched them melt.

To imbue masculine style, more usually formal, clubby and inexpressive, with warmth, style and delight was rare. It was also essential to the project. The room was not just for show, it was an experience for all the senses. Enjoyment did not depend on knowing it was good, as in art or taste, though it was that. It succeeded because grandeur yielded irresistibly to pleasure. Bernard infused the weight and richness of the Victorian style with the levity of the Edwardian to Romantic effect.

The single fireplace in the Octagon Room was replaced by the original pair, found hiding in the cellars, and Bernard discovered matching overmantel mirrors, framed in Carrera marble, in Lots Rd antique market. Mirrors were used to reflect and maximise light. In the dining room, natural light was enhanced by a huge mirror bought at auction from a Salvation Army hostel. The Staircase Hall was doubled in size when mirrors from Chelsea Glass were cut to a template and fitted in otherwise redundant arches.

Octagon Room, before

Octagon Room, remarbled by Laura Jeffreys

and hung with a collection of portraits including Ellen Terry, Alfred Tennyson, the 3rd Earl Somers and members of his family painted by G.F. Watts.

I went with Bernard to Watts of Westminster, ecclesiastical outfitters, to look at the archive. Bernard loved nothing better than to chance upon a fragment he could then work up. The wall covering and curtains in the Little Library were the result of such a discovery at Watts. We explored the wallpaper archive at Cole and Son and found a 19th Century fleur de lis on alizarin crimson which was block printed up for a bedroom.

Modern British and gothic: the Red dressing room, aka Lord Somers’ dressing room, with a portrait of stern Dorothy Mulloch by Spencer Watson and two works by Susannah Fiennes: Coles’ C19th fleur de lis pattern woven into wool worsted.

The Red Bedroom, Coles’ document hand-blocked wallpaper and the same pattern woven for a bed cover, bed remade from the elements of an Italian baldachin.

Context Weavers in Lancashire spun the same design into worsted for curtains and hangings. The bed itself was created from what Bernard recognised as a made up piece of furniture; pieces of 17th Italian century carving taken from a baldachin in the 19th Century and fashioned into a show case. The master craftsman Dieter Weber, a German prisoner of war who had returned and lived in a tower of the castle, took it apart and turned it into a four poster bed. The success of this dramatic room was proved when film star Harvey Keitel, and his girlfriend spent an entire weekend ensconced there, blaming it on the good karma. They were our first paying guests.

Bernard’s eye for decorative detail was exact. He knew the correct pleat of a curtain, the right height of a curtain pole above a window. I felt liberated when he told me skirtings and cornices did not have to be white, and coloured the ceilings too. My way of disinterring the spirit of the castle was to dig a bit deeper, first with the help of Edith Wharton’s anatomy of rooms and their purpose, ‘The Decoration of Houses’, and then by getting to know the people who had lived at Eastnor before me through the possessions and letters they had left behind. Bernard was also good at getting my former husband James to spend money, but not everything that he persuaded James to buy fitted this history. The first Earl Somers who built the Castle and was so overbearing that both his wives fled from him, would never have had Marie Antoinette’s bust at his elbow.

The third Earl, my favourite, would have preferred to be an artist. When visiting his friend GF Watts’ studio he fell in love with the striking beauty in the portrait he saw there and asked for an introduction. Virginia Pattle, sister of Julia Margaret Cameron, later great aunt of Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf, was so traffic-stoppingly lovely she could have married anyone, the 3rd Earl was ‘dwarfish – ugly too,’ but when he proposed, she accepted. They travelled extensively, to paint and also to collect Venetian art and 17th Century Italian furniture for Eastnor, having seen how well it looked in castelli. I was never sure he would have liked a row of plaster Caesars on scaglioli columns looking down on him – Eastnor is gothic! –

but to Bernard’s eye they were handsome – always a term of approval when an object caught his attention – especially young Marcus Aurelius.

Not all Bernard’s suggestions were successful; hanging a portrait over a perfectly good Flemish tapestry in the library because he had seen it done in an old Country Life photograph of Hardwick Hall was batty, and it quickly came down.

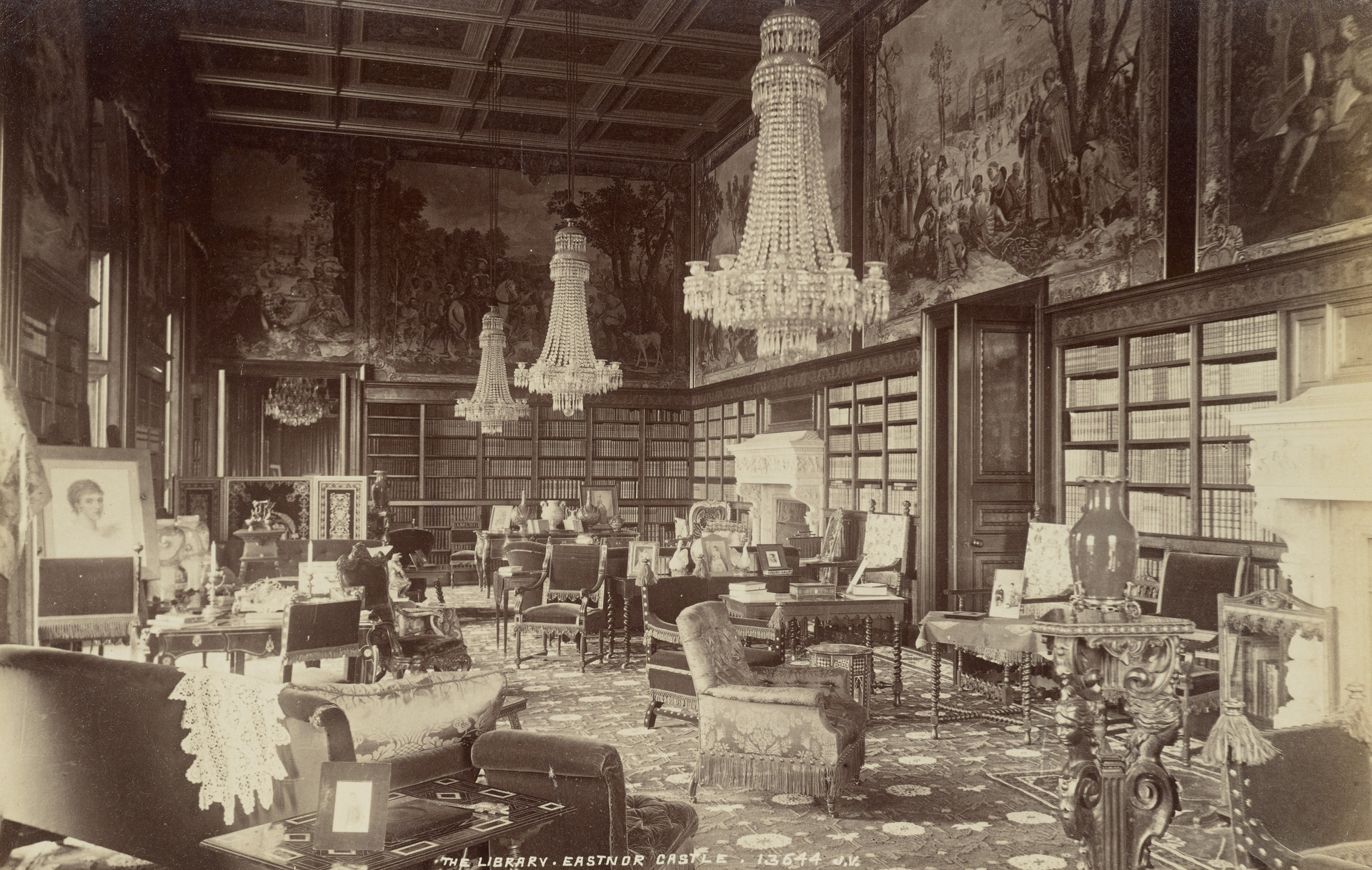

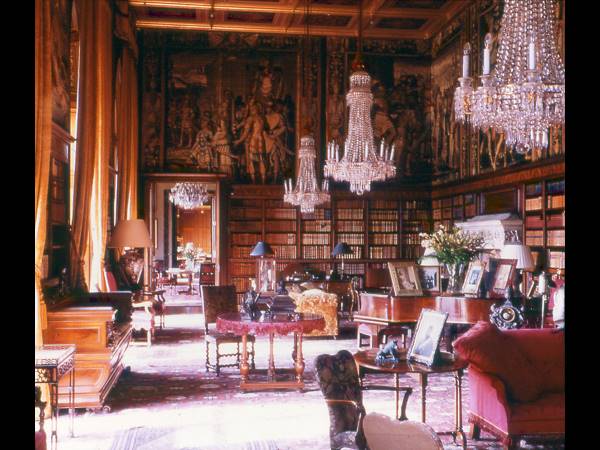

James Valentine, the tapestry-hung Long Library, C19th, National Galleries of Scotland

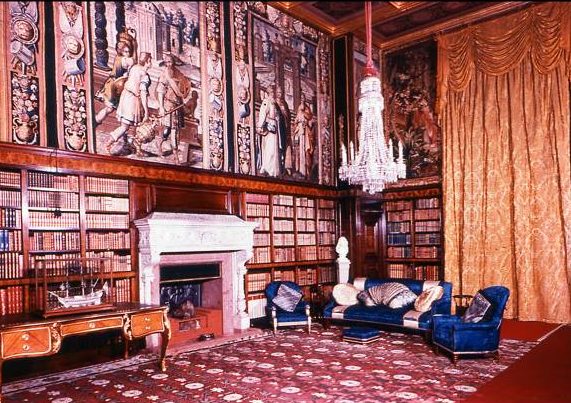

One of the advantages of the dimly lit and cold castle Eastnor had been was that tapestries were remarkably unfaded and the thousands of books in the library perfectly preserved, but this foible was as nothing when put in the balance with the benefits Bernard brought. When asked by James which of a set of three fabulous Bruges tapestries he should bid for at auction, Bernard said, ‘Buy them all!’, and James did.

The Long Library before redecoration

Long Library, after

Bernard and I shared a love of taxidermy. Eastnor was full of creatures from the African veld and Bernard recognised their gothic quality in his re-arrangement.

My own interest was more personal. As a child I had wanted to be a taxidermist, a wish springing from a love of animals and the paradox that by this means they might live forever. So when the tufted silhouette of an eagle owl appeared on the battlements at dusk, only to disappear just as mysteriously, before being brought to the back door, dead – it had flown into a pylon, we were told – we immediately asked local taxidermist Roger Brookes to bring it back to life. The great owl has cloaked its prey from the gaze of the visitors as they walk through the Great Hall ever since. Restoring a similitude of life in this way is not so different, it seemed to me, from breathing life into a house, or as Edith Wharton went on to do, bring people to life on the page.

Imari vases turned into lamps were particular favourites of Bernard and he taught me how a frame, tortoiseshell or carved ebony ideally, could be as decoratively important as the art it contained. He loved to dress a room, and I was surprised to learn that you cannot be too rough with flowers; he taught me how to pull apart a big bunch – nothing formal, an armful of cow parsley, viburnum or guelder rose would do– to create a sense of generosity and exuberance. When we arrived, the bathrooms were chilly with linoleum floors in the school cloakroom style.

Modern bathrooms were either marble tombs or extensions of the bedroom, but carpet and wallpaper quickly lose their looks when exposed to steam and stains. Bernard suggested setting the baths and basins into Forest of Dean sandstone and panelling the walls around them, reserving wallpaper for the architrave and laying rush matting on the floor; a solution at once handsome and practical.

We were very lucky to have the supremely talented Laura Jeffreys as specialist painter, introduced by Cath Kidston. Parts of Eastnor had always remained oddly unfinished and incomplete. Perhaps the third Earl, responsible for the historic decorative decisions, ran out of inspiration in the Staircase Hall: perhaps being an aristocrat in the 19th Century sometimes made it harder, not easier to get things done. Whatever the reason, the massive stone staircase dominated the empty, putty coloured space. Laura painted in the missing stone walls which were then hung with the Bruges tapestries and hatchments.

The Octagon Room, too, had a diffident air, painted plain eau de nil in striking contrast to the glories of the Pugin Room and the Italianate Long Library with which it formed an enfilade. Here Bernard found it hard to decide what to do, a predicament he shared with Laura who despite her skill and experience found taking a decision torture. This was due, she explained, to the divorce of her parents and the situation this created; if she chose what one wanted, she would inevitably disappoint the other.

Bernard wondered about painting each pilaster a different marble. I felt this would be overdoing it – far from a crime in his opinion – but in the end he agreed and Laura’s virtuosity was reserved for the ceiling panels.

The State Dining Room

Colour was the beginning of my collaboration with Bernard. The certainty that characterised his attitude seemed to abandon him when confronted with a blank wall, while colour in the right context was like oxygen in an airless room to me.

Pugin-esque curtains and dining room chairs designed by Eastnor’s architect, Robert Smirke

We chose the deep, rich blue of the Dining Room walls and the muted terracotta of the Great Hall together. The vast, vibrant crimson curtains in the Staircase Hall, made by curtain maestro Ian Block, possessed the vital quality that needed reviving at Eastnor. Bernard was primarily a textile designer so his hesitant attitude to colour surprised me. I put it down to the fact that he sourced his designs in rare and antique fragments that he then worked up. He always preferred a provenance, but his work was not derivative, he insisted, and to consider it so was ignorant. Instead those sensitive and culturally aware like himself picked up ideas and trends in the zeitgeist and interpreted them.

In between Bernard’s visits, perhaps six weeks apart, I was not idle. Ignoring current trends, I took my cue instead from the character of the rooms themselves. I sourced second hand (pre-‘vintage’) curtains and antique fabrics from Costume and Textiles sales at Christie’s South Kensington which were reconfigured to fit by Ian Block. By this means we hung the windows in a way that was individual to Eastnor and avoided the bad habit wives had at that time of feeling up the curtains and pricing the fabrics in each others houses (leg lifting was competitive).

Chinese Bedroom, decorated by Sarah Hervey-Bathurst

Pre-decoration, the Chinese Bedroom as a carpet store.

Being on the spot gave me an obvious advantage and I discovered that the body will keep going long after the mind has had enough (I was young).

The cellars

With James working in London and Birmingham and the children – Isabella was born in 1990 – in bed, I could plod about the castle into the night, taking objects from the cellars or pictures and old textiles from the attics to offer up in different locations. The familiarity I gained with both rooms and objects enabled me, over time, to realise instinctively where an object belonged, what a room needed, without having to offer it up. The Works Department was no easier – I was a woman after all – but I developed ways to deal with them; telling them that James had asked me to ask them to carry out a task, or taking a corner of the chest of drawers or table that needed to be moved to shame them into action as they stood thinking about it.

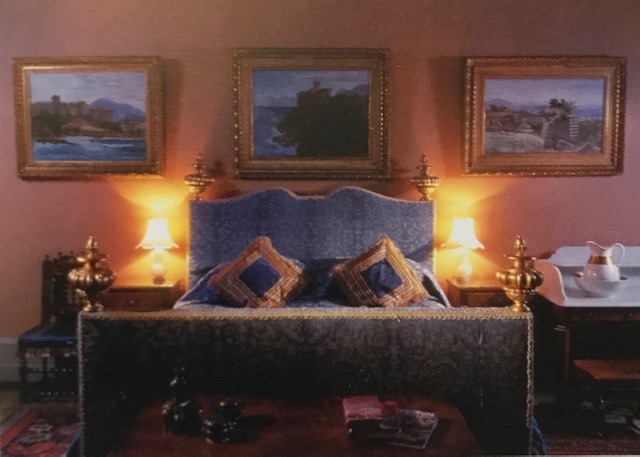

The Italian Bedroom, before

and after

Artists have a professional eye for colour and I deferred to the 3rd Earl in the Italian Room and Dressing Room. The sepia of the walls was taken from his moonlit Italian landscapes, and Laura mixed the woody blue of his Italian daytime skies for the walls of the dressing room.

Laura was even able to create colours that only existed in my mind until she realised them so exactly I recognised them instantly.

Smoking Room decorated by Sarah Hervey-Bathurst with Laura Jeffreys

I had always thought the richness of oil as an artistic medium diminished when a painting was hung on an expanse of chalky wall, and asked Laura to mix a deep yellow glaze to give the walls of the Smoking Room the timbre of oil.

The Family Dining Room, decorated by Sarah Sarah Hervey-Bathurst and Laura Jeffreys

Her exceptional talent also enabled her to recreate Philip Webb’s bough of cherries, embossed onto gilded leather for the William Morris café at the Victoria & Albert Museum, as a stencil. In the small (family) dining room she stencilled the leafy cherry boughs against their golden background onto the architrave above the dark panelling to make the east facing room lustrous and welcoming. Bernard was not involved in any of these decisions; he had many other commitments which meant he could not spend enough time at Eastnor to gain the familiarity I experienced or enjoy the serendipity that occurred when things start to fall into place of their own accord, a phenomenon I would not have believed had I not experienced it. I could have done none of this without Bernard’s bold example and instruction never to compromise, but my taste was not identical to his. Not so keen on the more feminine Edwardian, I enjoyed the natural affinity between the 17th and 19th century, the former adding the flourish of sensuality the latter lacked. I always preferred the painting to the frame and liked the way 20th century art added a dynamic dimension to the occasionally complacent past. I prefer things underdone to overdone, so it was perhaps to be expected that when Bernard saw what I done, he loathed it all. Luckily he was the exception, but the upshot was that after he left I never saw him again.

the Gothic Drawing Room, before

The purpose Bernard, James and I shared was to create, perhaps for the first time at Eastnor, an experience that everyone could enjoy. I was not brought up in a castle, I was brought up in a shooting lodge but if I could feel at home at Eastnor, I was sure others would too. The ‘at home’ feeling, the atmosphere, depends on much more than appearance, and the experience of Eastnor, whether guests were paying to stay or not, depended on Rosemary.

James Valentine, The Gothic Drawing Room, C19th, National Galleries of Scotland, decorated in the High Gothic Revival style by A.W.N. Pugin in 1849 for the 2nd Earl Somers.

Rosemary was thirteen and the eldest of three siblings when her mother gave birth to twins. Overnight she became responsible for the family cooking, cleaning and washing. After marrying and bringing up four children of her own, Rosemary was looking for a challenge. Lucky for the castle it was on her doorstep. Back to back house parties of twenty? No problem.

The Gothic Drawing Room (redecorated by Bernard Nevill in the 90s) is hung with six tapestries, four of them from Wimpole Hall, former home of the Earls of Hardwicke, one of whose daughters married the Second Earl Somers and brought the tapestries with her.

Three thousand visitors through the house over the weekend? Cleaning restored the karma. Climbing scaffolding to polish a regiment of arms and armour? She was up there. Nothing phased her. Rosemary and her team made the restored castle tick. She was the heart beat.

A perfect host, Bernard was an exacting guest. Was it five or six tiny leaves in the cup of vaguely tinted water he called tea? I could never remember, but Bernard could, and always told me when I got it wrong. He was a vegetarian before it was usual to be so and when my minestrone met with his approval he was as surprised as I was, but it could not quite make up for the half-day spent preparing it. He never hesitated to say when something failed to meet his expectations; ‘Disgusting!’ was an epithet liberally applied to anything. ‘Marvellous!’ – it’s opposite – only rarely bestowed.

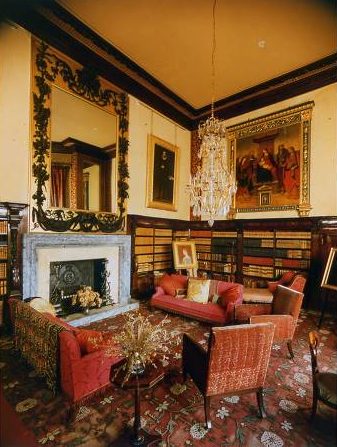

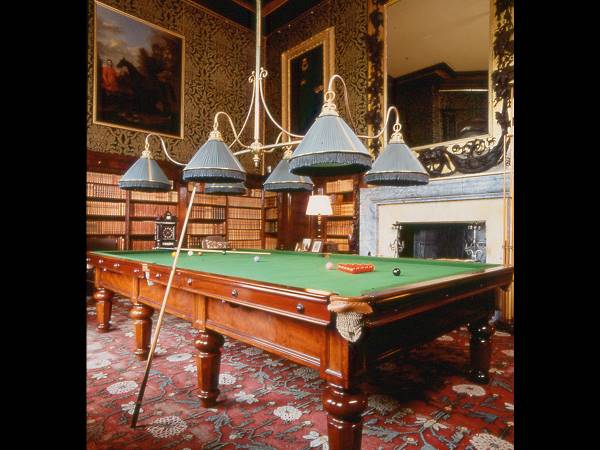

The Little Library, before

He was something of a snob and enjoyed talking of ‘Tally’ this and ‘Tally’ that, when Tally to me was just a nice, sporty girl in the year below at school, not a duchess. Perhaps his attitude was due to the psychological foible he recognised in himself but to his regret could do nothing about; he could only enjoy an experience retrospectively, never in the moment itself.

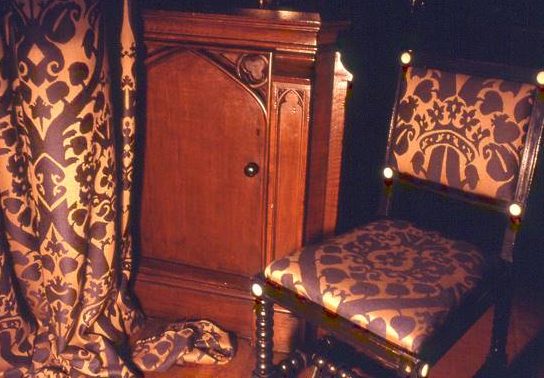

The Little Library, after: fabric for wall hangings, curtains, and upholstery chosen by Bernard Nevill from document designs in the archive of Watts of Westminster. The billiard table, put into store in 1939, was brought back and reassembled in 1990

Despite this, he appeared to enjoy playing a game with our daughter Imo when it was still acceptable for an adult to be bored by small children. ‘Where’s Imo?’ he would say, ‘Where’s Imo?’ pretending not to see her hiding behind a chair, catching our eye as he laughed at himself for playing the game, ‘Where’s Imo?’ Imo would giggle and he would feign deafness and blindness, casting about for her in his capacious coat until she burst out, unable to contain either her excitement or his inability to discover her. For her fourth birthday, Bernard gave Imo a princess costume. Naturally Bernard’s princess was not any old Cinderella, Imo was to be an Indian princess. Thrilled, she flew about the great rooms of the castle like a dart of shocking pink fire.

State Bedroom, original hangings on the walls and bed, bed cover made up from a pair of old curtains

The State Dressing Room, redesigned by Sarah Hervey-Bathurst as a bathroom.

The Places like Eastnor are much bigger than the individuals briefly attached to them who come and go. Both Bernard and I are part of the castle’s history now but the narrative continues with the skills and hard work of others.

In memory of Laura Jeffreys, whose life was cut short, but whose talent to transform lives on at Eastnor.

All photographs by kind permission of James Hervey-Bathurst, archive photographs copyright National Galleries of Scotland. Grateful thanks, and especially to Sarah Hervey-Bathurst for writing this memorial and Isabella Hervey-Bathurst for additional photography.

This was such an interesting post. I am so glad that I read every word as it so enlivened the pictures which I would never have appreciated otherwise or truly understood. Thank you.

Absolutely fascinating, terrific text and fabulous photography, especially for someone like me who trained in fashion & textiles. Am going to forward it to all my textile designer friends!

Re reading this a second time, wonderful stories. When studying at St Martins in the early 70’s I lived in Glebe Place but never met Bernard which I regret. The area was filled with amazing personalities and I remember poetry readings at Leighton House in costume. One day Vincent Price gave me a tiny black kitten that turned out to be completly bonkers and ruined the house so I gave it to another Gleber who kept monkeys and snakes and the cat, named Osbert Sitwell, fit well in. I then found another tiny kitten under a lorry in Chinatown and named him Sacheverell. It was an incredible community, never replicated as it wasn’t as conscious as our present day versions.

I really enjoyed this! Sarah, you did a wonderful job decorating the in-between spaces. The Chinese bedroom in particular turned out beautifully!

Really enjoyed reading this. I visited Eastnor today and was curious about it. Marvellous finding all this information on the web. Well written too!

Great read on a lazy Christmas Day researching antique furniture. Thanks for taking the time to write this piece and the great photos..what an amazing place. Next time in the Cotswolds, must make a trip over.

I have a ‘mystery’ chair that once belonged to Bernard that am trying to learn about.. Originally at West House in Glebe Place that then took with him to Cheyne Walk. Hoping maybe something that could suggest a name of either designer or maker if send an image or can see (its the only chair) on my Instagram page; artewedes

Thanks.